First Published in

It’s an ad joke. If you want to sell something without trying too hard just add in sex, puppies or children. These visuals appeal to the very deepest nature of man, but in a new world where puppies and children are considered passé and the media factory around us has become more and more obsessed with sex, where exactly do we draw the line and who decides where that line is?

Back in the 1950s a man named Vince Packard wrote a booked called The Hidden Persuaders, an honest and untainted account of the very clever social engineers who figured out how to sell (and create) products by appealing to people’s subconscious desires. At the same time, the Freud family and Edward Bernays became involved in trying to create a “model consumer” through the spread of “good” propaganda. These seminal studies gave birth to a new type of advertiser, known as “depth men”, a breed that rather earnestly believed that products could make life better for the individual and family.

Over the next 20 years these researchers and their offspring discovered that one of the most effective ways of shifting units was to quite simply add sexually charged imagery – regardless of the product. This is not too hard to understand: after self-preservation, sex is our strongest urge. When this imagery is used we respond on a physiological level, having a truly moving experience. Without being consciously aware of it, our heart rate increases, we begin to salivate (even more so if the colour red is used) and, if you are a woman, your breasts swell by up to 25%.

Unfortunately for advertisers the portrayal of sex in advertising can’t happen without gender being brought into the picture. In a country like SA where we have a smorgasbord of cultural norms, the differences between us become truly heightened when presented on a media platform that is supposed to appeal to millions.

Take Lolly Jackson, owner of Teazers strip club. Not a man you would assume knows the difference between sex and gender, he still managed to step over a very definite line with the Caster Semyena ad. The ad shows a stripper (an educated guess) reclining naked, one arm placed over her one breast, the other breast exposed, plus nipple. The headline reads: “No need for gender testing!”

The Advertising Standards Authority of South Africa (ASA) was alerted, the ad was pulled and Jackson didn’t even fake his glee at the amount of publicity he received, fuelling the furore further by saying: “I do not want anyone coming here [to Teazers] with the idea that we do not have women. We have women, 100% women here. I did a test on them, I am a professional and they are 100% women.”

The ASA has a hard time. Between über-conservative grannies in Bloemfontein and award-hungry agencies in Jo’burg and Cape Town, there is a very real need for a consumer watchdog. According to their database of just more than 2 000 complaints received last year, approximately 326 complaints related to gender alone – roughly 16%.

Says Leon Grobler, dispute resolution manager at the ASA: “You have to keep in mind that advertising should always be viewed in context. For example, if a TV ad showed topless women during Barney the Dinosaur, it would clearly be regarded as inappropriate. However, showing the same commercial during one of those late night soft-porn movies might not be cause for concern. I think our society is dynamic by nature, and as societal and moral values change, so does advertising content and people’s reactions thereto.”

Besides consumers, clients also serve as watchdogs. Net#work BBDO Johannesburg’s proactive advert for the 2009 Marie Claire “Naked” issue was declined when presented to Marie Claire editor Kate Wilson and editor-in-chief Vanessa Raphaely. On her blog, Raphaely said: “It’s intention was to draw attention to a feature that we have done in the latest Marie Claire, which poses the question, has fashion and advertising gone too far? I thought they’d missed the point. Marie Claire, of all magazines, speaks to both the good angel and evil devil perched on all our shoulders. It does not shy away from the controversial or challenging. But, it always treats women as heroes.”

So, the creatives found another outlet, slapped a new logo on and put the ad online, ostensibly to advertise cherryflava.com, but honestly to try and win an award. Interestingly, in the comments section there is fair comment on the way that the woman in the ad has been portrayed, but more commentators wanted to have their say about how the ad industry goes about their business.

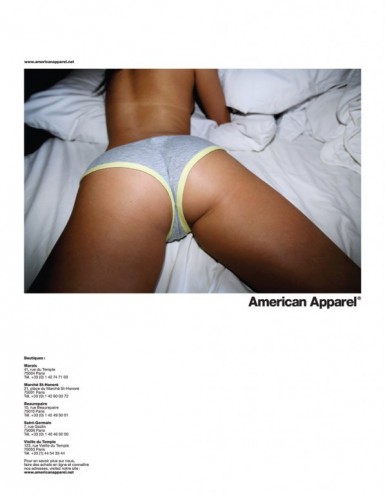

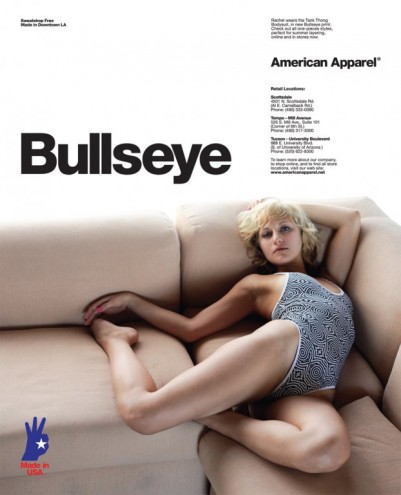

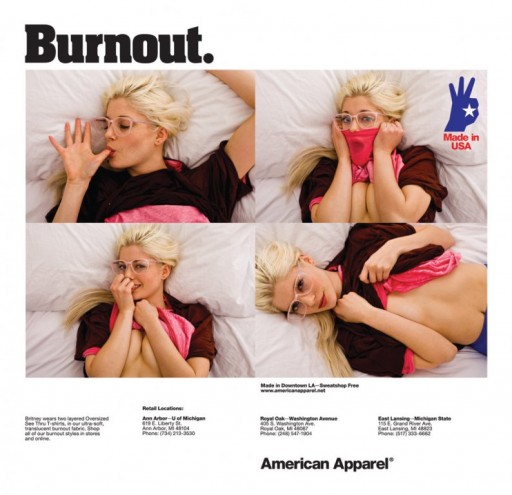

So, what about the business of intentionally targeting you with material that slips past your moral radar? It appears that if it’s tastefully executed we don’t seem to mind. Take American Apparel. Modelled exactly on 1970s porn poses, lenses and everyday-looking models, this home-clothes and underwear brand uses extremely explicit poses. However the ads are shot in such a way that the content seems homemade and therefore does not read like an advert. The communication feels personal, the models make eye contact with you (daring you to stare back) and you can be voyeuristic without feeling dirty. The only advert that has been banned was one recently, where the model looked distinctly underage.

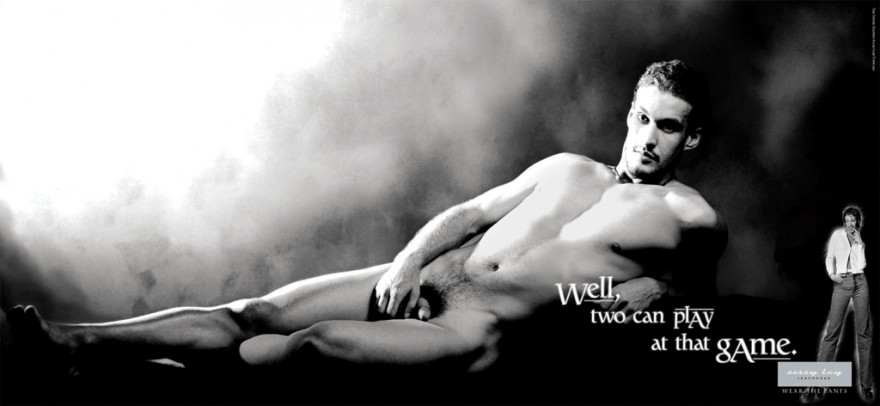

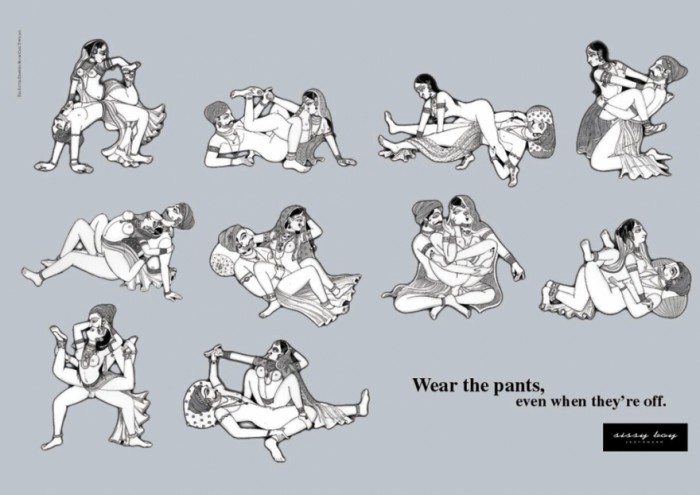

Most importantly, it’s passing under our radars because we like it. Interestingly, there’s a lot of very homoerotic advertising that completely bypasses many straight people’s blinkers. Considering that many people are still homophobic, you would think that ads like the D&G porn-shoot campaign and the Abercrombie & Fitch street ads of football players with bulging crotches, would rouse some discomfort, but in consumer research people read the images as “boys having fun”, “male bonding” and “frat party”. Since the early 1990s with Calvin Klein’s groundbreaking jocks and jeans campaigns, to the three massive crotch shots of men in Jockeys currently on the N12 in Johannesburg, the general consumer is truly becoming less reactionary.

To get a response, innuendos just don’t seem to work anymore. Nowhere is this more apparent than in beauty and fashion advertising. “High fashion”, by its very nature, is meant to be provocative. While the Calvinists may be having heart failure the rest of us are ogling (and sharing) the green penis in Paris’s sex tape, watching SMS ads on late night TV that are way more pornographic than the actual porn they are couched between, and not even blinking in music videos where women (usually the singer) are caged, whipped, killed, tied up, beaten or dressed to look like underage children, stuffed animals or are touching themselves in ways that will have tweens (girls especially) heading for the bedroom to experiment.

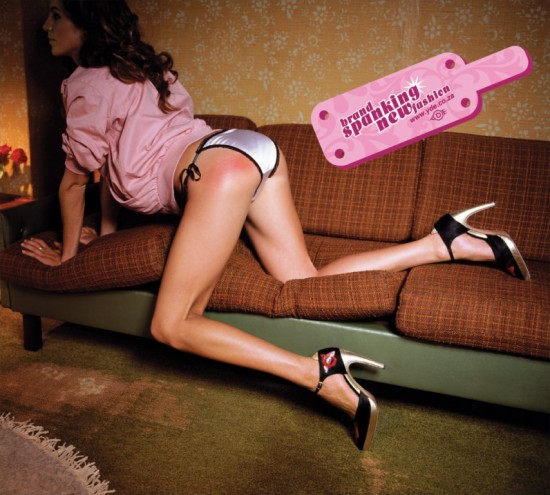

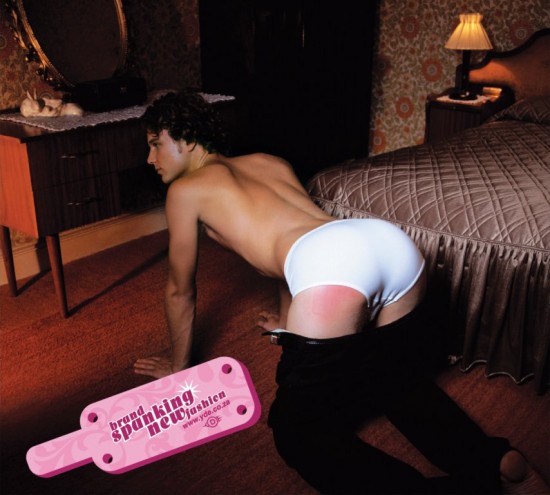

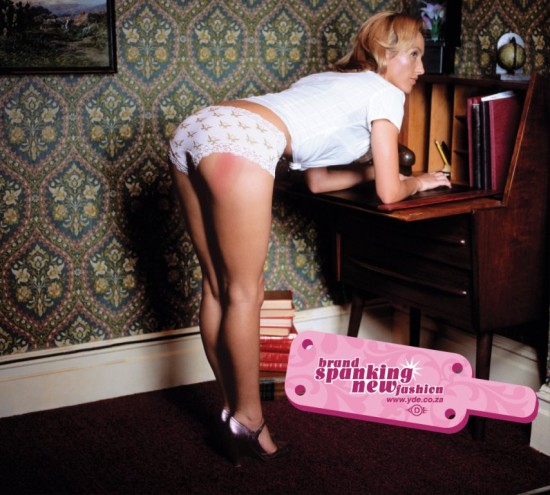

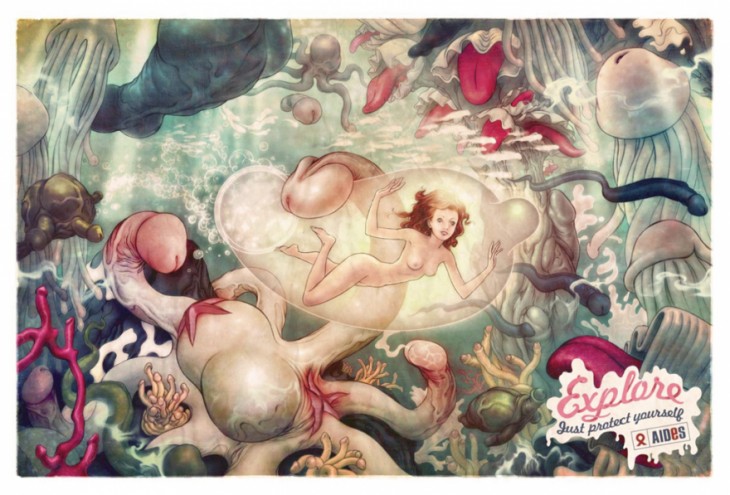

With all this clutter, advertisers need to work even harder to shock us into paying attention. What has been, up until now, a true taboo? Fetishes. The odder it is, the more arresting, the more interesting to peer at, the less likely we are to feel retribution. After all, you haven’t actively sought this image out. And so in the last few years we’ve become normalised to this branch of pornography. The XO whip-etched backs in Diesel’s campaign, the high-heels doing skin damage in Sisley, the extreme bondage in DSquared and the various incarnations of role-playing… Is there anything at all that could shock us?

The Clinique cum shot is a classic example. There are two ways to read this. The product is targeted at women (not even the tertiary audience is male) and yet they have used a picture that appeals mainly to men. It’s a pretty sexist but fair assumption to say that more men fantasise about coming on a women’s face than women dream of having it done to them. What is even more sexist is the advertiser’s assumption that women will buy the product because they are being told that this is what men like, and that by owning the brand or product they may possess some of that magic formula so desperately needed to snag the right Alpha Male. Having said all that, the actual advert wouldn’t have converted to direct sales, but the surrounding publicity helped with brand recognition and recall to the yellow goo that you will find in all Clinique moisturiser ads.

You’d think that after well over 40 years of feminism, modern women would be offended, but a backlash has come in another form. More and more, women are portrayed as sex-hungry, sex-ready and a little desperate, a construct that sends us right back to Freud’s ideas of female hysteria and women needing to be cured (read quietened) through the use of the medical vibrator. Forget Third Wave Feminism and Grrl Power, chicks are heading for Raunch Culture. From female chauvinist pigs in the States to the ladettes in the UK, young girls are choosing to behave like boys – or behave like they believe boys want them to be.

So how does this visual language translate at street level? In South Africa our rape statistics are some of the worst in the world and the use of a condom is still considered unmanly. Here the ad industry really does step up to the mark – even if only to win awards – with our PSAs (public service announcement ads) being some of the most hard-hitting and highly awarded work in the world.

The question we need to ask ourselves is: Why, if we are happily over-exposed to high-gloss, shiny smut in the world of fashion and brands, do we feel distinctly queasy when it comes to portraying the really dark side of sex?

Recently for the 2010 Soccer World Cup many agencies focussed their proactive efforts on creating ads to address the problem of human trafficking and slavery, two issues directly linked to the sex industry. Saatchi & Saatchi created a freaky toy game for the Salvation Army where you could choose your own child, complete with a little card telling you how and when they were stolen.

Childline also continues to do great work through their agency, but it is a message that many people don’t like to hear. An ad from a few years back shows a black-and-white photo of a young girl. Underneath she has filled out a form in her childlike scrawl: “Name: Kim. Age: 6. Sex: 9 times.” Their current TV ad is just as chilling, with an opening sequence of a fatherly-looking man doing up his zip and belt followed by a close up of a small girl in her bed, now alone, and very upset.

Unfortunately, LoveLife, one of the most important of these campaigns, has been a documented failure. In the first stage of the campaign the main objective was to reduce HIV infection by 50%, a goal not for the faint-hearted. The problem at the time was a lack of communication between children and adults and so the team settled on the line “Talk About It”. Bizarrely, in trying to talk about sex they chose to use complex and convoluted semiotics, leaving even the most ad-literate befuddled. By the second stage of the campaign major national and international funders had pulled out, saying that the campaign had become “incomprehensible”.

Most likely the normalisation of sexually charged images will continue to proliferate. This is not necessarily a bad thing – the more normal sex and sexuality is considered, the more normal our behaviour should become. It’s the space where sexual deviation, consumer manipulation and subtle exploitation blur that we need to keep our eye on.

The situation is less perilous than it could be. The number of women working in the creative industries is fast approaching the halfway mark and men are becoming increasingly aware of what it feels like when the tables are turned. All we have to do is say no. No, I won’t make that advert. No, I won’t buy that product. No.