Imagine the inside of a gallery at night: deserted, dark and quiet. Imagine the art works in shadow, except for perhaps a little moonlight. Then imagine having exclusive access to that. For five consecutive nights in August 2014, digital product design studio The Workers was able to take more than 100 000 people wandering through the Tate Britain after hours. And they achieved it all with the help of four robots.

After Dark, the name they gave the project, won the IK Prize 2014, which celebrates digital creativity, supporting ideas that present a new way of enjoying art. The project allowed viewers all around the world to control the robots as they roamed around the Tate Britain between the hours of 10pm and 3am. The Tate’s resident experts also provided live commentary on the art through the web.

The Workers sought the help of RAL Space (who are currently working on the Mars Rover) to build the four robots, which made for a rather extraterrestrial experience. Fittingly, famous astronaut Chris Hadfield was the first to test drive one of them.

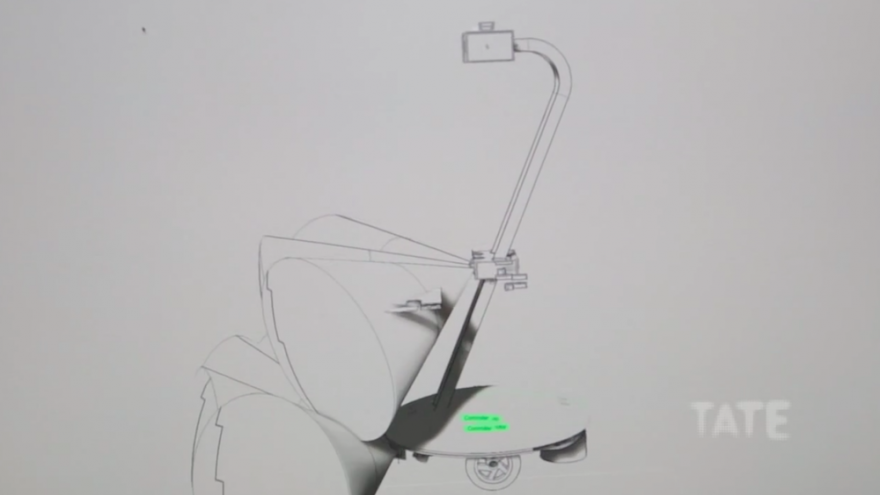

Each robot was outfitted with intelligent sensors and sonar navigation devices that would prevent them from bumping into any illustrious pieces of art. Two low-light LED torches and cameras were fitted to the robots’ heads, which stood no higher than that of a small child, and could be pivoted up and down and swiveled from side to side.

After Dark transformed the Tate into a vault of treasure that anyone could explore with the robots’ eyes and torches. The viewer doesn’t get a perfect view of the artworks, but what they do get is the opportunity to see the Tate’s collection in a different light.

The duo behind The Workers, Ross Cairns and Tommaso Lanza, will speak at Design Indaba Conference 2015. We asked them for the story behind their After Dark project – and what's become of the robots since their late-night jaunts around the museum.

Had you ever worked with robots before?

This was our first time. Thankfully the After Dark robots are quite simple from a robotics standpoint. We like to think of them as a creative solution to a well-defined problem. The few things they are asked to do, they do very well.

What was the project you were working on in the Tate before After Dark?

We were heavily involved in the creation of Bloomberg Connects for Tate Modern, for which we designed and wrote all the software. It is a multi-faceted installation spread across three floors of the gallery. The system allows visitors to post feedback about their experience in the gallery, take pictures of themselves, make drawings on a giant projected wall, etc. Some of this data (photos, drawings, quotes) then trickles back into tens of screens arranged over the stairs that connect all levels of the gallery.

How large were the robots? Were they the height of a man or a child? How fast could they move?

The robots are about 1.2m tall. Besides technical reasons, the view from that height does instil a sense of childlike exploration. The robot’s head can also tilt up and down, which sometimes contributed to quite dramatic viewing angles with some of the artworks.

What kind of emotional response did you get from people watching?

The response form the audience blew us away. The excitement on Twitter was palpable. People sent us beautiful messages as they were waiting in the virtual queue, hoping to be handed control of a robot. We also allowed people to leave a message upon entering the queue. Some of those messages were true expressions of excitement and others were quite moving, in particular those from people who didn’t live near a museum or hadn’t seen one in a long time.

What surprised us was seeing the robot's behaviour change starkly from person to person, just by looking at the live video feed. Some people were more cautious, others more curious, some more interested in the art, others just piercing through the dark in search for the next doorway. And the robots absorbed and exaggerated these expressions of personality.

As per ourselves, it was a turmoil of emotions, from excitement to concern, to awe and surprise. We only had a few chances to run full-scale tests before going live, so you can imagine what it felt like when hundreds and then thousands of people started watching the event.

How long did After Dark take, from its conception to the nights the robots went wandering?

We had six months from the initial announcement, and it took us a solid four months of production work. There is a lot more to it than software and hardware. Thankfully the Tate team has been an incredible partner throughout.

Where else would you like to send the robots?

If you can think of any place that is access-restrained, that would be it. Although the robots were customised for Tate’s specific environment, our dream is to see them deployed in many different places, and not necessarily in their current form.

It may be more museums, scientific organisations, theatrical performances and spaces, or even live TV broadcasts. The level of openness, interactivity and control that the system creates can be lent to almost anything.

Where are the robots now? Are they being used?

We left one at the studio watching over the other four disassembled ones. As we write this we are in Berlin setting up an installation for the Fashion Week.

What was the biggest lesson you took away from After Dark?

In a way it proved that we can trust our instincts. There were a lot of things that needed to be answered pragmatically. Building five machines and a complex software stack in four months, plus all the ancillary tasks in between – all of it with a team of three. The technical and creative possibilities are endless and it is all too easy to get carried away. It happens to everyone, and this was a lesson in reduction and simplification for both the concept and the execution. We had to narrow our focus on the core idea because of the combination of limited time and the profile of the project, and the final result owes much to this.

The project also shows how accessible some of the technology involved has become, and how independent small teams can now produce amazing feats that would have previously required much larger commitments.

Do you think it is strange that the path to intimacy with art was through a machine?

Great question! Some people who wrote about After Dark thought that we were trying to build a way of experiencing art “from the comfort of our homes”, as a window to the future of museums or a surrogate of a real visit.

Instead what we were looking to create was an open-ended experience. A means to break into a restricted location. A unique occasion to experience the gallery in a way that is not comparable to a traditional visit. And we know After Dark made people feel very close to the space they were exploring. In those short 12 minutes the audience owned the gallery as they were wandering about, pointing their avatar’s eye to the artworks and the darkened doorways and rooms.

During one of our first tests we walked into a room to see a robot staring up to a 500-year-old portrait. The subject in the portrait appeared to be looking back at the robot and it felt like an oddly personal exchange. Two distinct ways of portraying reality were colliding in the same space.

The machinery in After Dark is the interface to an experience, much like the oil on a canvas is an interface to someone else’s vision. In many ways After Dark is an open medium rather than a tool built for a particular task.

Do you think that to help people experience something in a new or profound way it is useful to alienate them first (with the unfamiliarity, the robot, with the darkness, etc)?

That can help, although there wasn’t a conscious intent to alienate. The experience of controlling a robot from the web is per se alien to most. If anything we tried our best to make it as easy as we could so that people could enjoy most of the short time they were allowed in. There was limited time for each person and we wanted everyone to enjoy the most of it.

When the two of you work together, do you split tasks equally or do you find that you naturally take different roles?

It depends on the project we are working on. For more complex projects we tend to plan in advance to avoid doubling up on tasks. Sometimes each of us is responsible for a single project and others it’s a very organic, less structured process.

How do you complement each other?

While we have gently overlapping skills across the board, each of us has different areas of expertise. Ross is very comfortable with code experimentation, unafraid of breaking things to make them better. On the contrary I [Tommaso] tend to have more of an analytical approach, which perhaps stems from the highly constrained world of industrial design. This creates a strong creative and intellectual tension and it feeds each other’s curiosity.

The Workers will speak at Design Indaba Conference 2015, which takes place from 25 to 27 February 2015. Book here.