First Published in

“If true computer music were ever written, it would only be listened to by other computers. I think this is an inherent limitation that we prefer to ignore,” wrote Michael Crichton mysteriously in his book Electronic Life, published 1983.

Seeming to describe a parallel universe of artificial consciousness that humans would never access, the quote encapsulates the existential questioning of early-1980s technoculture; a period of abundant innovation when personal home computers started gaining consumer traction (10 years after invention) and the first TCP/IP network (ie the internet) was prototyped in 1983. In 1984, William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace” in his cyber-punk novel Neuromancer as “A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators.” Everything was just so radically novel…

Oh boy, remember those heydays of leisure technology? Back when eight-bit video games gave you futuristic goosebumps? When on TV they used to say, “Let’s go to the tape”? When mix tapes were all the rage and the Walkman was the iPod? What did you write in your first email and who did you send it to? Remember your first 1.3mp digital camera and that old brick of a cellphone? Remember when they were two separate devices? Or the day your gran had to finally just throw away her Beta video player and there was a funeral feeling to the afternoon?

It’s been a long time since I’ve had that feeling, although over the past 10 years I’ve probably gone through at least eight cellphones, three iPods, five PCs and four digital cameras. But who can blame me, you or anyone else – things get more efficient, break earlier, improve functionality and become obsolete, faster and faster. Who cares about technology anymore? If there were a “ghost in the shell”, the past decade would be quantified as a technological holocaust.

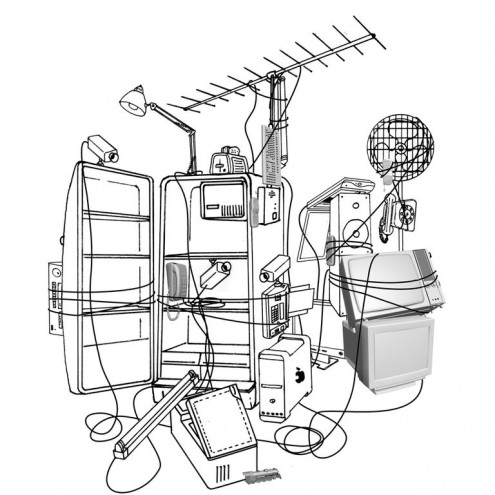

Even if only a nostalgic throwback to a few decades ago, what if gadgets do have souls and computers do make music for each other? Would we care more for them then? Turning up the volume on electromagnetic fields, Troika’s Electroprobe is a magnetic microphone to the parallel universe of electronic gadgets and appliances, allowing us to eavesdrop on the “electric babblings, magnetic hums, inaudible whistles” of our mostly taken-for-granted digital compatriots.

“Quite a while ago, objects started to speak. With time, they grew smarter. They now have a rich vocabulary. They think and dream. Electronic brainwaves. Organic signals. Bluetooth monologues and wireless fantasy. They talk, exchange opinions and sometimes argue,” explains the Troika website.

Troika are a London-based multi-disciplinary art and design practice founded in 2003. Electroprobe was their first work – the result of Sebastien Noel’s Masters degree project in the Design Interactions course at the Royal College of Arts. Fellow students Conny Freyer and Eva Rucki make up the triumvirate. Initially bringing their finesse in exhibition, installation, graphic and animation design to Troika’s work, Freyer and Rucki helped to expand the Electroprobe concept to create electronic orchestras. Basically, electric appliances like cellphone chargers, clocks, DVD players, computers and other gadgets are all hooked up to Electroprobes to create sonic landscapes.

Since then, over the past seven years, Rucki tells me over a good-old telephone, that their roles are less defined, with all three organically involved in the whole process from research and conceptualisation, through functionality and manifestation, to presentation and exhibition. Their work includes a number of installations and interventions in public spaces and galleries, a handful of products, some graphic design, and two books. The most recent book, Digital by Design (2008) surveys the growing genre of work that reimagines the relationship between technology, design products, immersive environments and human interaction for the 21st-century – the genre of design in which Troika themselves work.

Even though Troika have gone on to make high-profile work for the likes of MTV and British Airways, Electroprobe fittingly remains one of their favourite works – “It’s a gateway into another world that is invisible and it is intriguing in that it is a tool that gives people access to something that surrounds them, but that they haven’t thought about,” explains Rucki.

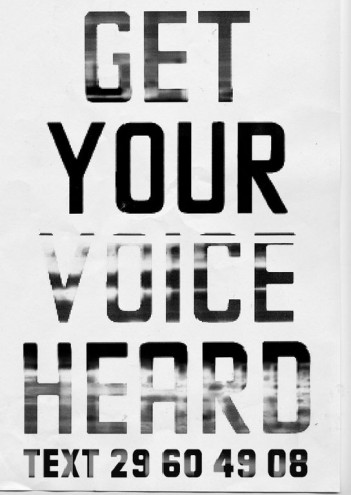

Revealing the invisible and reviving vintage technology, Electroprobe is a physical manifesto for the underlying aesthetic and conceptual prerogatives in all of Troika’s work. Sonic Marshmallows are site-specific sculptures in a park that amplify whispers over 60m. When installed in a public space, the Tool for Armchair Activists shouts out SMSes allowing for remote rants and demonstrations, while the SMS Guerilla Projector allows users to project SMSes onto public spaces. And, my favourite, the TV Predator is a jealous picture frame that will ambush the amount of attention bestowed on TVs by randomly messing with the TV’s functioning.

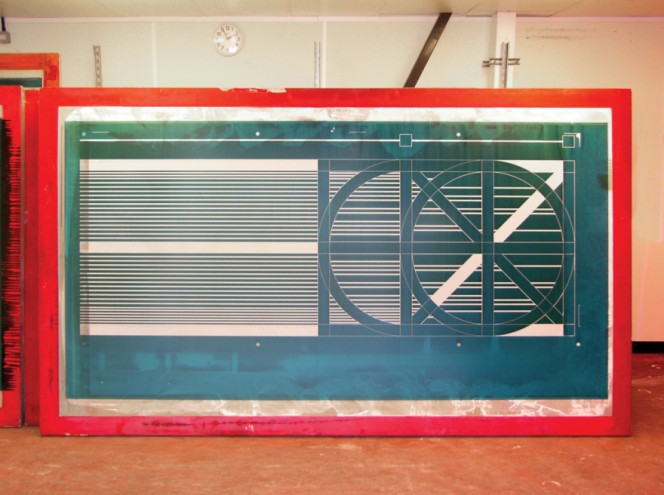

Although the projects may sound anarchic and underground, purveying a steampunk sensibility, Troika have managed to breach the corporate gap by keeping it all very light-hearted and tasteful. The All the Time in the World installation at Heathrow links to far-away places, exotic wonders and forgotten cultures through multiple world clocks using the technology typically used in electronic alarm clocks. In turn, The Cloudin Heathrow revives 1970s flip-dot technology to create mesmerising waves of magnets chasing across the surface of the sculpture.

“Technology now is about ‘no restraints’ and ‘bigger, faster, better’. We find it very interesting that in older technology there are still restraints and boundaries. Often we make these our challenges and see how we can push them, rather than using contemporary technology where everything is possible,” explains Rucki.

Wikipedia tells me that, in response to the inefficiencies of the 1950s split-flap display, the dot-matrix flip-dot display was developed and patented in 1961 and first used in the Montreal Stock Exchange. By 1977, over half of the world’s stock exchanges and many shop fronts, cars, road signs and train schedules were using them. But, by that time, LCD displays proved more efficient and started becoming the default choice.

Is “bigger, faster, better” the only function of technology? This is Troika’s challenge to design’s perceptions of limitations. By recontextualising flip-dot technology, it becomes an object of beauty and wonder, inviting you to remember your personal gadget graveyard. In turn, by reviving the stalled development of the electroluminescent segment displays of alarm clocks and the like, Troika multiplied the old-school seven-segment display to a 7 000-segment display of varying shapes in All the Time in the World. With 7 000 segments, it can display up to five different fonts and some captivating motion graphics. Interestingly, this development has more than simply aesthetic implications – the display is only 1mm thick and uses a fraction of the electricity compared to the text-displaying plasma screens throughout the rest of the airport.

“I think that technology carries the inherent promise of some finality in itself. Then you have to ask how functionality is designed and which roles it should be fulfilling – the basic needs or the upper levels of Mazlow’s pyramids or even other desires of humans, that are more intellectual,” agrees Rucki.

There are more questions than answers in Troika’s work – and they’d be pleased to hear that. At a time when no one can quite figure out how the mantra “reduce-reuse-recycle” can overwhelm the prevailing philosophy of incremental improvement, everyone must reevaluate the notion of obsolescence. What if we could posthumously accrue a different function to so-called obsolescence?