First Published in

It is said that most people use only 10% of their brain and only one side, depending on the skills that they need most. So what happens to the 90% that isn’t being used? For one person at least, it would seem that the other 90% is a steadily puffing industrial district dishing out fully-formed ideas like pies from its shop front – the visible 10%.

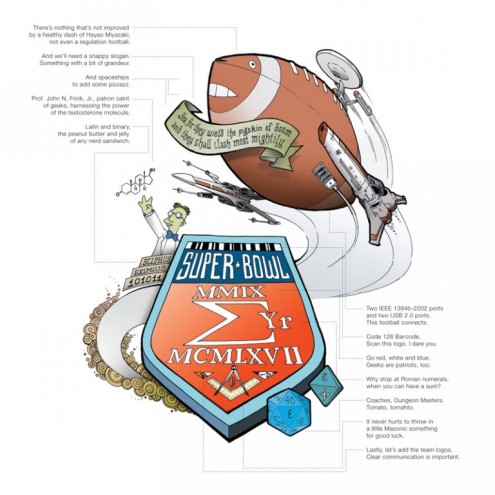

While most of us have an idea, stop, think about how good it is and then forget it a minute later, Stefan G Bucher’s thought process resembles an infinitely looping assembly line, on which a multitude of ideas are continuously being tweaked. To put it simply, this graphic designer doesn’t just conceptualise and dismiss; he tries to find a suitable application for as many of his ideas as possible, whatever the medium – from complex flow charts about the notions of love and the worldwide success of the Daily Monster, to the humble art of album covers and the painstaking perfection of typography.

Bucher worked as a freelance illustrator in his home country of Germany before moving to California in 1994. In 1998 he founded his own graphic design company, 344. Since then he has worked on numerous projects, turned many others down and acquired a small bunker of awards. In 2006, his cerebral assembly line gave birth to the Daily Monster phenomenon when Bucher breathed outrageous life into a splatter of ink. After filming himself drawing the first one, he ended up filming himself for the next 99 days, posting a new monster every night, and drawing a community of monster obsessives that collect and create stories behind each of his creations.

I had always hoped that my own 90% was a 500°C furnace where my wayward ideas could be tossed and ignited into Superideas. Meeting Bucher, I realise that my approach was all wrong; everything, every little wayward idea, could one day grow up into a Superidea, as long as I don’t burn them alive! Still I’d like to believe that occasionally the whistle blows and production comes to a standstill, but Bucher doesn’t have the time to rest and it doesn’t seem he wants to. After all, who could blow the whistle when the next Superidea could be at stake?

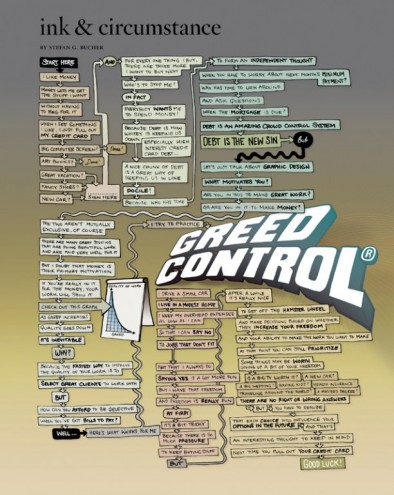

Your work ideal is strongly based on your idea of Greed Control®. Can you explain your philosophy and how you manage to live by it?

The easiest way to improve your portfolio is by choosing great clients. If that choice is motivated by a desire to produce great work, your portfolio will reflect that. If your first priority is making money, you’ll see that in the work too. As greed increases, the quality of the work goes down. It’s all about having the freedom to choose who I want to work with. For me, the only way to get that freedom is to practice Greed Control®: I keep my overhead costs as low as possible and my envy of the material success of others to a minimum (that’s the really hard part), so that I can afford to say “No”, both to new and existing clients.

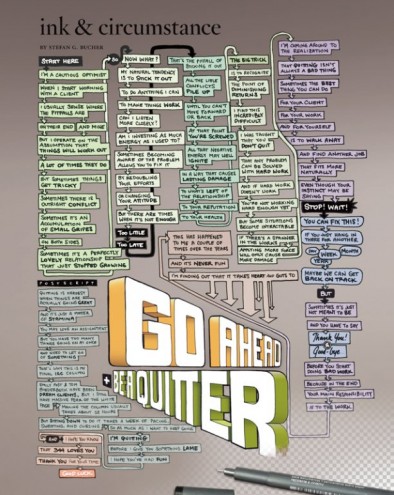

How do you decide which projects to take and which aren’t worth the time? Have you declined doing any worthwhile projects that you regret?

At this point they seem to have a pretty good idea of what I do, so when people invite me to help, it’s usually on great projects. I don’t have to say “No” that much anymore. If I do, it’s usually only because I only have two hands. I don’t regret passing on any of the great jobs I’ve had to decline. For some reason or another they weren’t the right fit, and I hope that I’ve always been helpful with finding a great match for those clients. What I do regret is that I didn’t have the right set of skills and circumstances to do the job myself. I’m always honoured that people want my help on their projects, and I’m sad when I can’t give it.

What is it about design that keeps you intrigued and wanting more?

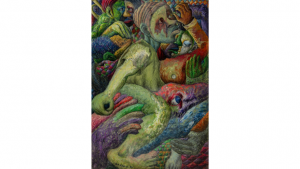

I love absorbing information – art, music, nature – and giving shape to the ideas and opinions that form because of it. Design is one of the ways in which I express that, but others include illustration, writing and my talks. When I design something, it’s simply my opinion of what that information should look like. What keeps me intrigued and wanting more? I see and hear new things every day that prompt new ideas, and I’m working as hard as I can to get those ideas out of my head and into reality.

You’ve gone from designing CD covers to book covers to catalogues – just about every medium you can put your hands on. How do you manage to slide so effortlessly through all these channels of design?

“Every medium I can put my hands on” is right. Every medium and format has its conventions. Once you learn those, you can bend a few rules, overthrow a few others, but there are always ideas you can’t get produced in a particular format or context. Often those are the things that become the start of what I’ll do in a new niche. One of my art teachers told us never to clean our brushes all the way, so a little bit of one painting would go on to the next.

You say that ideas just pop into your head constantly and almost play around with you. How does that influence your design process and the various projects you’re involved in?

It drives me. I feel responsible to the ideas I have. I’m their guardian and I want to make as many of them real as I can, because I feel guilty about those that I let evaporate again. I keep lists of ideas that I haven’t produced yet, so I don’t forget. But even with that, it’s much easier to jump on an idea when it’s fresh in my head. At the same time, I’m a professional and know when to put my blinders on. One completed project is worth more than a dozen that stay half finished.

Daily Monsters has become a worldwide phenomenon, but it’s in fact quite a personal project for you. What has it been like watching something so personal become such a widely absorbed, watched, collected and admired event?

It goes hand in hand. Had the Monsters stayed a completely personal project, I might have stopped long ago. But because they got so much love and energy from all the people who came to the site to post stories and drawings of their own, they became as fun and interesting as they are. Having this great, active audience also kept me focused, especially early on. Getting so much kind reinforcement from everybody gave the Monsters more life than I ever could have on my own.

What is incredible about your work and your ethos is that you design independently. Your studio 344 Design is literally only you. What are the challenges you face and the opportunities you gain working alone against corporate agencies?

The great, overwhelming benefit is that I have almost total independence. I need very little money to keep my doors open, so I can be very picky about the work I do. I also have the freedom to work on things like the Monsters. The challenge is that I’m limited to doing only the things I can think to do, and that I have the time and energy to produce on my own. I often wish I had a support staff, but then I’d also have to take on work I’m not 100% crazy about to keep everybody fed. This is why I love consulting for larger design firms and ad agencies; they’ll bring me in on projects where my ideas can be useful, and I get to work with brilliant people using the power of a “Big Machine”.

Your approach to design is somewhat eccentric and fantastical. What is the philosophy behind your design process and where does it stem from?

Well. I appreciate the compliment – those are great words to have next to my name – but my approach never seems eccentric or fantastical to me. This is just how I see the world and what I do is the clearest, sanest response I can think of.

What do you believe has contributed to your significant success as a graphic designer up against so many other graphic designers?

I don’t think it’s a zero sum game. I don’t see myself competing with other graphic designers. My race is only with myself – doing the best I can do with the means at my disposal. I try to make things that I think are interesting and fun, things I’d want to see. That’s all I can think to do and I work extremely hard at it. I’ve been lucky that so many people enjoy the results.

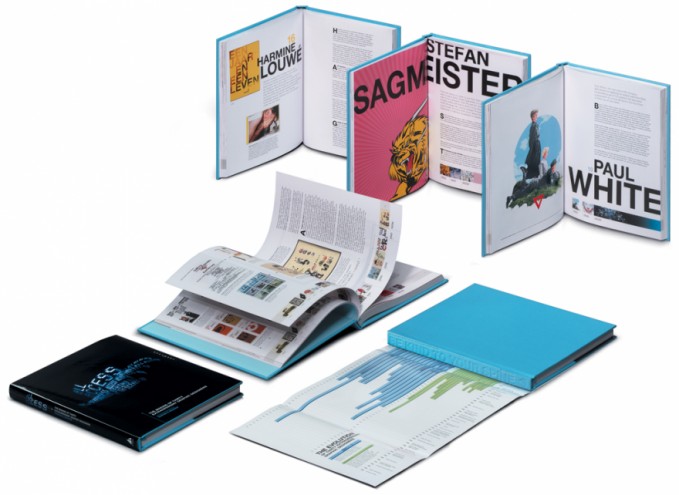

You’ve won a number of awards for your work. What are your thoughts on winning awards for something that you love doing? What do awards mean to you?

I love the things I make, and I work hard to make them with as much care and integrity as possible, so that they’ll be useful to people who take the time to enjoy them. Like everybody, I also love a pat on the back, so I enter design shows. I’ve served on a whole bunch of design juries too. By now I know the dynamics of that situation and have a pretty decent idea of what projects might do well. Some of my favourite pieces would never get the votes, because they’d come off as too slight, silly or simple. Others, I know, will do really well. But juries are hard to predict. I’ve been in rooms where everybody was of a mind and it’s been a lot of fun putting together an interesting show. Other times nobody can agree on anything and the result is sort of a mess. But in either case, I’ve never experienced a group of judges that didn’t approach the job with care and a serious desire to honour the best work regardless of pedigree. So when a group of great designers all agree with each other that I deserve an award for a piece, I’m always excited and proud. And when I scratch out, I don’t take it personally. For too long.