First Published in

We live in unprecedented times. Never before has there been the demand for people to go about the business of being human in ways that ensure the continuation of all life on the planet. Up until fairly recently, there was always the assumption that life, including our own genes, would go on and on without us having to do anything more but get on with our lives in the present. Nowadays, as the dangers of climate change and mass extinction loom, our interdependence on all the rest of life is much more apparent.

However, as the natural capital we depend on declines at ever-increasing rates, we are still battling to comprehend the scale and complexity of our accountability. We’re still grappling with the enormity of what it is to transform every modern human system to become sustainable. It is a fair argument that we are in dire need of innovative tools, practices, frameworks, arts and sciences that help us to live the lives we aspire to sustainably.

One of the most exciting and inspiring disciplines that has emerged over the past couple of decades is biomimicry. Natural sciences writer and innovation consultant, Janine Benyus first coined the term and presented biomimicry as a practice for sustainable human innovation in her influential 1997 book, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. The word derives from the Greek “bios” meaning life, and “mimesis” meaning imitation. Since then there has been an increasing pool of innovators from diverse fields – designers, engineers, architects, managers, developers and business leaders who use biomimicry as a tool to create sustainable designs for products, processes and systems.

Benyus recently featured in BusinessWeek’s list of “27 of the World’s Most Influential Designers”, in 2009 she received the United Nation’s Champion of the Earth Award for Science and Innovation, and she has been honoured by Time magazine as one of the “International Heroes of the Environment”.

Nature as model, measure and mentor

Biomimicry invites us to forge a new and different relationship with nature by recognising that we have far more to gain from learning from nature, than extracting from it. When we use nature as model, we study the genius of sustainable designs, processes and systems in order to draw inspiration and, in so doing, imitate nature to solve human problems. When we use nature as measure, we access an ecological standard based on 3.8 billion years of evolutionary design intelligence. Nature knows what works and what will last. When we use nature as mentor, we shift from being autistic and illiterate in our relationship to life, to being ecologically intelligent, inclusive, participatory and, potentially, sustainable.

Practising biomimicry in its fullest form is a virtual tour through a systems-worldview. For instance, if you study the model of the feather of the owl with the aim of unlocking the secret of silence in motion, you will be organically led to the understanding of the owl. Knowing the owl will lead you to understanding its relationships in its ecosystem. Knowing the owl’s relationships in its ecosystem will lead you to understanding the ecosystem, and all its components and networks. Knowing how an ecosystem works will illuminate the principles of life that we need to adhere to if we are to remake our world as sustainable.

In a society accustomed to disregarding and trying to dominate nature, the prospect of an intimate and respectful relationship may be uncomfortable, even fearful. In this context, biomimicry is a radical and revolutionary approach. But it is also just plain common sense. As Benyus points out: “Life manufactures, computes, does chemistry, builds structures, designs systems and engineers, to within a fine tolerance, the tools needed to fly, burrow, build dams, heat or cool homes and so on.” Whatever we need to do to sustain our lives, nature already does. How can we ignore this? By regarding nature as model, measure and mentor, we can tap into a deep and vast store of sustainable living wisdom and expertise that we sorely need.

Biomimicry in practice

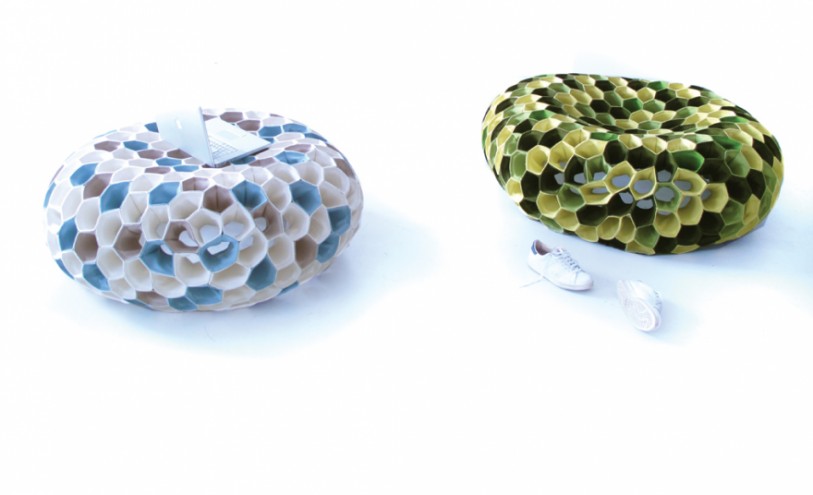

One may well consciously emulate a natural design, but true biomimics do so with the goal of using nature’s genius to achieve a sustainable solution to a human problem. Biomimics look to the surface of the lotus leaf to design self-cleaning traits without harmful chemicals; to the abalone to make durable ceramics without expensive, polluting heat; to the peacock to display gorgeous colour without toxic dyes; to the mussel for stunning adhesives without any poison at all.

Nature offers a cornucopia of intriguing design solutions relevant to the span of modern human endeavour, from enhancing performance to achieving efficiencies by fitting form to structure; from self-assembly to timed degradation; from feeding on carbon dioxide to self-medicating; from harnessing water in the most unlikely environments to growing food like prairies.

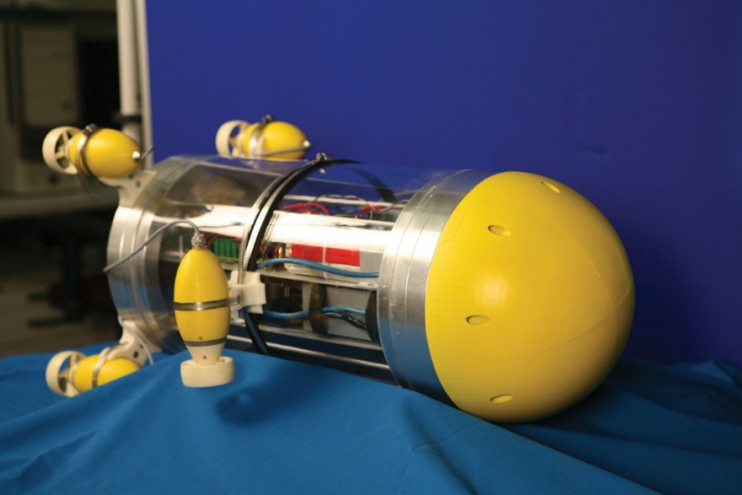

The brilliant blueprints of butterflies and bacteria, whales and tardigrades, diatoms, brittle stars, seals and sea sponges are all offering us invigorating solutions to some of our most pressing problems.

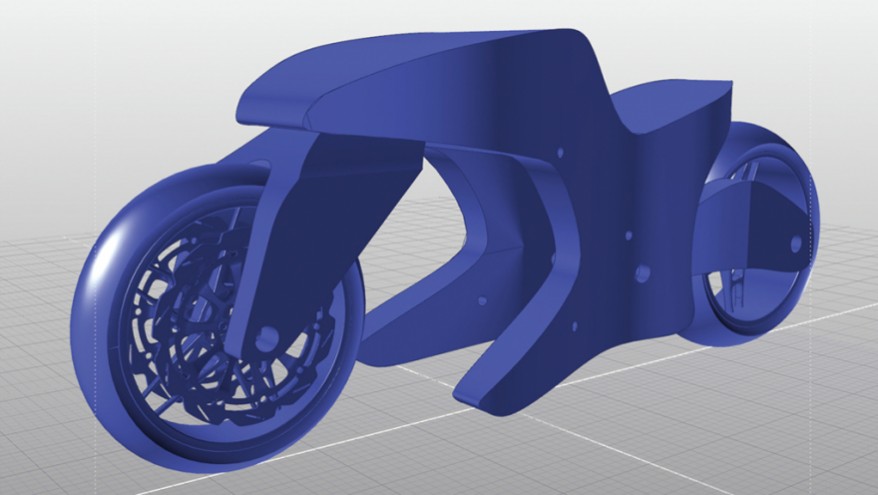

None of this is just theory. There is a building in Zimbabwe based on the design of a termite mound that maintains a near constant temperature without power. There is a desirable outdoor jacket that mimics the waterproofing and warmness of a seal’s fur. There is a high-speed train with a nose fashioned after a Kingfisher’s bill that increases efficiency and eliminates the sonic boom. There’s always new news about biomimicry as more and more innovators discover, research, imitate and apply another of nature’s grand designs.

Biomimicry community

South African design practitioners and educators are fortunate in having a vibrant, emerging biomimicry hub that connects us to the worldwide network. The South African Biomimicry Network is headed by Claire Janisch. In conjunction with Benyus’s Biomimicry Institute (www.biomimicryinstitute.org), introductory courses, tailor-made workshops and presentations are readily available in the country. Various projects are also underway to include biomimicry in our high school and tertiary curricula.

Designers and design educators can also join the global biomimicry network “Ask Nature” (http://asknature.org) to access latest case studies and connect with both biologists and designers who are intent on using nature as model, measure and mentor to bring about a more sustainable world.

In our current crisis of unsustainability, design educators, working designers and other innovators who know what sustainability is, who understand how life works and who work according to life’s principles are most likely to emerge as the most valuable designers and innovators on the planet.