First Published in

Over the past 100 years we have seen urban populations expand at an incredible rate. More people now live in cities than ever before, so much so that soon two out of every three people on the planet will live in one. By 2020 more than 20 cities will have passed the 10-million population mark and nearly 600 cities will have a million or more inhabitants.

The problem has historical and economic roots. In the UK, thousands of rural dwellers moved en masse to urban areas during the Industrial Revolution to man the large factories and mines that were developing throughout the country. These jobs came with higher wages than could be earned as farm workers or rural labourers, and so gave rural people an opportunity to improve their economic situation.

The move from rural to urban areas today is still in the main due to economic necessity. People unable to scratch a living from the soil move to urban centres in order to find work, and so we now see many cities in the world populated not by indigenous inhabitants but migrants.

The desire to move from rural to urban areas also has a sociological cause. The need to provide for the family is clearly a primary motivation, but disenchantment with life in the rural areas, and the lack of opportunities to develop as individuals within perceived narrow social guidelines, often contribute to the desire for change.

As populations move out of rural areas, life in both rural and urban areas becomes more difficult. In many parts of the world these economic migrants find themselves living in homemade accommodation on the periphery of many of the world's large cities.

Often illegally sited, there are frequently no adequate energy supplies or sanitation facilities for these communities. With little social infrastructure, and often no state law visible, many of these areas become semi-independent states within states, sometimes ruled by criminal gangs. Barely educated, some of the occupants of these areas become involved in criminal activities in order to survive.

As many of these migrants come from different cultural areas we also see the replacement of traditional norms of behaviour with a homogeneous urban culture. The culture of survival replaces older traditions, which made it possible for people to live together in smaller communities on a more equitable basis.

There is no doubt that in many cases the move to urban areas provides some hope of a better life, but as populations migrate to these urban centres, rural communities become unsustainable. With many of the young men and women gone, many communities lose the social cohesion that held them together. Traditional ways of life die away, and old skills passed down through generations disappear.

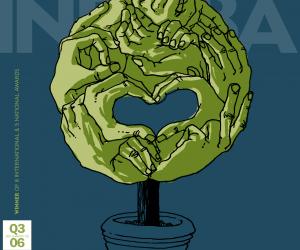

Cities are now enormous parasites, consuming the resources of regions vastly larger than themselves. Like most parasites, cities give very little back to the vast landmasses that supply their needs and bury their waste.

Although cities occupy only 2% of the earth's surface, they consume 78% of its resources. For example, the land area needed to supply the needs of the city of London is 120 times larger than itself. Although London covers an area of 1,500 sq km, the city actually needs 20 million square kilometers of territory to supply its needs. London is home to just 12% of the population of Great Britain, but it uses up the equivalent of all Britain's productive land to provide its services.

Around the world, the move from rural to urban centres has seen the development of many problems. In some respects, many of the health and social issues that we encounter in large urban centers today have their roots in these economic migrations themselves.

In many parts of Africa, for example, the need for labour required by expanding economies resulted in mass migrations of young men to urban centres. Under colonial rule in Zimbabwe and South Africa, these workers were not allowed to live within the centres of cities but were forced to live in overcrowded, squalid and poorly designed worker hostels on the outskirts of towns. These conditions, both physical and social, have caused problems that will take decades to resolve.

The move from rural to urban centres clearly has an effect on both areas. These effects can be seen around the globe with disenfranchised urban populations, eco systems struggling to support these vast communities, and empty and underused rural wastelands.

Is there any way of stemming this flow of economic migrants? Is there any way of giving people reasons to stay in their own communities and thereby reverse the trend of the emptying rural areas? Is it possible that a sustainable design approach could provide opportunities for individuals to stay within their own rural areas, and thereby stem the tide of migration to urban centres, which continues unabated?

To start with we must first look for a definition of sustainability. When the western world talks about sustainability it is not about the sustainability of the planet or of its resources, but the sustainability of the western way of life as the main motivational factor. The emphasis is therefore on how economic growth and personal levels of consumption can be maintained or even increased by utilising sustainable practices. By reprocessing metal and other raw materials we can create more fridges and cars from recycled materials, by growing trees we can offset the carbon emissions from factories that create these consumer goods.

The other definition of sustainability has to do with continuation of the low levels of consumerism found in many developing countries. Ironically, in some ways, by helping to keep consumer levels in the developing world low, the west is allowed to continue its particular way of life without hindrance.

Many international agencies are aware that with regard to the latter definition of sustainability, many of the underdeveloped countries lead the way. We only have to look at the consumption level of the average citizen of the USA compared to that of the average Indian to see that this is indeed true.

The traditional craftspeople of the world have always understood the importance of conserving resources. As raw materials are often collected locally they have always been aware of the dangers of overuse, and so manage their production accordingly. When looked at from an economic point of view these traditional craftspeople make sure that there is always a regular supply of raw materials to carry out their activity.

Small-scale enterprises such as these therefore enable livelihoods to be made without degradation to the environment, and therefore give viable economic alternatives to rural communities. Most traditional craftspeople by definition are therefore already working sustainably by managing their local resources effectively, and making sure that they always have the necessary raw materials to carry out their practices.

One of the problems of developing these small industries is, in some cases, lack of vision within governing bodies. Traditional crafts are often seen as being part of the past instead of one of the tools in creating an independent indigenous future. People who understand and value these crafts are often the craftspeople themselves; however, having little power themselves, they often have no opportunity to develop their business or creative skills.

Around the globe small-scale rural development programmes run by local NGOs are helping to address this situation. Agencies such as Aid to Artisans (operating in a number of countries in Africa and Central and South America) and ASSET in Gambia are helping to develop business skills among traditional craftspeople. These craftspeople - by creating work for themselves and others - are creating viable economic alternatives to urban migration. They are also ensuring that important aspects of creative traditional culture are being passed down to the younger generation.

Development programmes have helped to create a growing demand for rural products, and that demand often comes from countries that have been unable or unwilling to develop their own indigenous craft businesses. Sustainable small-scale design industries are therefore not only already helping to keep people from moving to urban centres, but are also helping to preserve, for the future, traditional skills that one day could be the bedrock of thriving community-based international businesses.

About the author

After many years of helping to develop small-scale industries in Africa, designer Carl Harrison is presently involved in developing the International Design and Education Association. (IDEA) based at Nottingham Trent University in the UK, where he is a lecturer. This is an association of International Design Education and Development agencies working towards sustainable design solutions of the future.

Apart from forging manufacturing links for trade associations that are looking for partners in the developing world, the IDEA is also involved in developing training programmes for traditional craftspeople and larger industries.