First Published in

“Press in India is the child of the freedom struggle,” says Palagummi Sainath, the award-winning Indian journalist. “Anybody with a vision, an idea, a cause and 50 rupees (US$1) could start a newspaper – which meant that everybody did.”

“Rebels started many of today’s [mainstream] newspapers. “[The press] was anti-colonial and anti-imperialist – that was its raison d'être.”

But what started out as a nationalist entity has changed dramatically in the last few decades. For Sainath, the trajectory has been paradoxical: “A tiny, narrow press in 1893 served a gigantic social function, it spoke for hundreds of millions. Today, a giant Indian media serves the narrowest of social functions – it is for the elite of the elite on the elite.”

From its origins, evidenced in the thousands of pamphlets and leaflets circulated at the time of the 1857 Great Uprising against the British, Indian press had grasped its readership, striking at the heart of a nationalistic-minded people. The ban of these pamphlets was routinely sought, by the British, on the grounds of their being seditious.

Concern over what was dubbed the “Nationalist Press” prompted the British Empire to request that Reuters – the independent news agency – dispatch a special correspondent to India in 1896. The correspondent’s role was something of a pre-cursor to the modern-day spin-doctor. He was essentially sent to do “a brush-up job for the Empire” by reporting on the “good works of British administrators,” says Sainath.

The need to enlist a reporter to reinforce England’s dominance was telling of the sway that nationalist Indian media had, the journalist believes.

“Literacy rates in 1893 were negligible and circulations were statistically negligible, even among the literate. It astonishes me how such a tiny, feverish press could place the world’s largest empire on the defensive to the extent that they needed Reuters to build them up.”

By the 1920s up until India’s independence in 1947, anti-imperialist press had reached critical mass, when a large number of mainstream newspapers – a number of which are still in existence – were already in circulation.

British-owned newspapers were in operation, but it was the vanguard of India’s independence movement that propagated nationalist media in the country. “Journalism and freedom were quotients,” says Sainath. “Anybody who was anybody in the nationalist movement was also a journalist.”

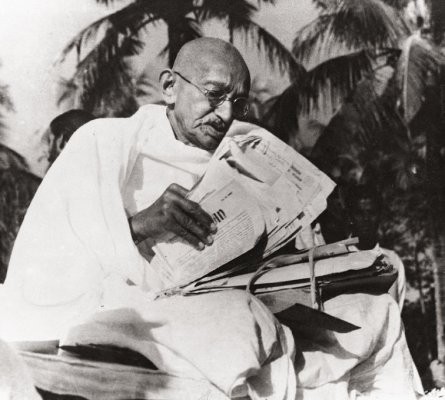

“Not many people realise that professionally speaking, Mahatma Gandhi (often called The Father of the Nation) was India’s most prolific journalist of all time.”

“He started three newspapers and every day had to worry about the ink, the newsprint, frequent shutdowns by the British, withdrawal of electricity and every kind of harassment. That was the journalist of the time; if you were a freedom fighter you were also a journalist.”

At the left end of the spectrum, Sainath explains, Bhagat Singh, the revolutionary whose untimely execution at 23 inspired thousands of Indian youth to join the independence movement, was a prolific writer. And when newspapers wouldn’t run his stories, he’d bombard them with letters. Female leaders – Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit and Sarojini Naidu – were also journalists who started publications.

For Sainath himself, with a career in journalism stretching back three decades, the veteran scribe has been privy to the huge changes in the Indian media since the early 1980s.

“The fundamental characteristic of the media of the last 20 to 25 years is the growing disconnect between mass media and mass reality,” he says.

“It shows by any measure that you care to apply. If you look at the beats that reporters have, [India] the country with the largest number of absolute poor, does not have a single full-time reporter on the beat of poverty.”

He is critical of the disproportionate coverage of issues, stressing the need to have full-time correspondents dedicated to covering housing, agriculture, labour and education.

Labour reporters active in the 1980s have become extinct and the agricultural correspondent is a phenomenon he likens to the yeti: “sightings now and then, but no confirmation [of their existence].”

The proliferation of fashion, design, celebrity and sport correspondents structurally reflects what Sainath says is an elite-orientated media, alienating some 75% of the country’s population – the poor.

“In the last 20 years, the Indian elite are in an incredible, unending love affair with themselves. Don’t you see it? Every day, some third rate NRI (non-resident Indian) in the US wins a fourth rate award at a fifth rate festival somewhere – it’s front page. The narcissism of the Indian elite is nauseating beyond belief.”

Sainath says that this shift in the media’s focus came about in the early 1990s, when India entered the liberalisation and globalisation period.

“Until then, even the worst newspaper paid some lip service to the issue of poverty,” he says.

“Once 1991 came, with it came what I call the ‘great betrayal’. The elite intelligentsia, the newspaper world and the media world completely broke that historic, organic link between the media and the masses and moved into covering the top five percent of what I call, ‘the beautiful people.’ At that point I decided that was very traumatic, and if that’s what the media was going to do, then I was going to cover the bottom five percent.”

As the rural affairs editor of The Hindu – India’s third most read English daily – Sainath spends on average 270 days a year working in the countryside.

However, he acknowledges that he is something of an anomaly is the journalism world: “The kind of journalism I subscribe to, I still do, but most journalists don’t have that option or space. I’m very privileged and lucky.”

The concentration of media ownership gained momentum in the 1980s and has greatly impacted the face of Indian media.

In the 1930s to the 1950s, says Sainath, colourful, eccentric individuals were at the helm of most newspapers, steering dialogue and debate into the issues of the time and reinforcing Indian ideals, particularly relevant around the country’s independence. This press was hugely diverse.

Gradually, newspaper owners were forced to sell out to bigger business interests that today continue to consolidate and grow bigger, he says. The result is what he calls “canned sardine journalism,” a homogenous press.

“Today a newspaper owner has 500 other interests: he’s in shipping, steel, cement and the Internet. Any law that the government makes affects him, so he will lobby vigorously without telling his readers why he is taking that position.”

Another shift in the last 50 years of newspapers has been the steady scale tipping away from a circulation base towards advertising space. This trend, Sainath considers, has been as devastating to Indian media as it has been to the global news industry.

“The newspaper world that saw itself as the defender of the underdog, that saw itself as a voice for the voiceless, now simply sees newspapers as a revenue-maximising industry.”

As an industry, print media has grown exponentially since the 1990s and according to the National Readership Study (2006) over 220 million Indians read dailies and magazines.

With more than 20 officially recognised languages in the country, a huge number of Indian language newspapers have emerged to cater to rural and regional language readers. In Hindi alone, the combined circulation of dailies is over 40 million, which is over twice that of India’s largest English newspaper, The Times of India. As it stands, rural and urban readership is largely equal.

Robin Jeffrey, an expert of Indian press and author of India's Newspaper Revolution: Capitalism, Politics and the Indian Language, has his own observations, saying that press has never been more accessible to the poor and non-English speakers.

“Indian-language newspapers get fairly close to the grassroots,” he says. “There are plenty examples of small-time stringers on the take, and of big-time proprietors extracting big sums for favourable coverage, but there are also lots of examples of small people’s stories getting noticed publicly as they never would have done in the past.”

In a press that he characterises as a “mixed-bag,” Jeffry does however emphasise the need for the country’s media to play a watchdog role.

“There are big deficiencies in Indian journalism – in training, in bribe-taking, for example – but it is hard to see how they can be overcome except in the course of other media outlets exposing them,” he says.

But for a journalism practitioner like Sainath, the changes witnessed in the last 30 years have diluted a freer, more diverse press than that which he joined.

Despite reports of a thriving Indian press, Sainath is far from convinced of its impact. Instead, he proffers the example set by Gandhi.

“Size and direct reach were not the only measure of impact. If that were so, Mahatma Gandhi would have amounted to nothing. His print order for his journals was miniscule, but he came with a moral authority (that marked that journalism), which forced every single pro-colonial and pro- or anti-nationalist newspaper to engage with and debate [with] him. He was read out to people in every corner of the country. How do you measure that reach?”

For Sainath, being a journalist is embedded in the freedom struggle legacy of this country, a legacy that he believes is important to recall for its values and the way in which it empowered the ordinary man.

“The freedom we have came to us because of the defence of our rights by those masses, not the elites. It was not the elite who was protesting, it was illiterate workers and peasants more often,” he says.

“The ordinary folk of this country created a space for us.”