First Published in

By February 2001, the South African government had spent R40-billion on new housing programmes. Between 4,5 and 5 million South Africans have received "secure tenure" homes since 1994. It is a level of delivery that surpasses that in Cuba, Singapore and Sweden, countries regarded as benchmarks throughout the world. Source: M&G, 23 February 2001

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of people living in poverty. Nearly half of its population - or 300 million people - live below the international poverty line of US$1 a day. Between 1990 and 1999, the number of poor in the region increased by one quarter, or over six million per year. If the trend continues, Africa will be the only region where the number of poor people in 2015 will be higher than in 1990. Source: The Development Goals in Africa: Promises & Progress, UNDP and UNICEF Report, New York, June 2002

South Africa accounts for about 60% of Africa's wealthiest individuals, with 24000 millionaires sharing US$300-billion among themselves. Source: World Wealth Report

We are no longer optimistic. Not like they were in 1914.

It was then that a bold Italian architect confidently celebrated the virtues of modern architecture. He said it would be an architecture of calculation, of audacious temerity and of simplicity; an architecture of reinforced concrete, of steel, glass, cardboard and textile fibre. It would perforce shun wood, stone and brick, indeed all the elements of nature that the ancients drew inspiration from for their art.

"We who are materially and spiritually artificial," wrote Antonio Sant'Elia in his Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, "must find inspiration in the elements of the utterly new mechanical world we have created." And that is exactly what we did. We built countless cities principled on things that "endured less than us", vast spaces celebrating impermanence and transience.

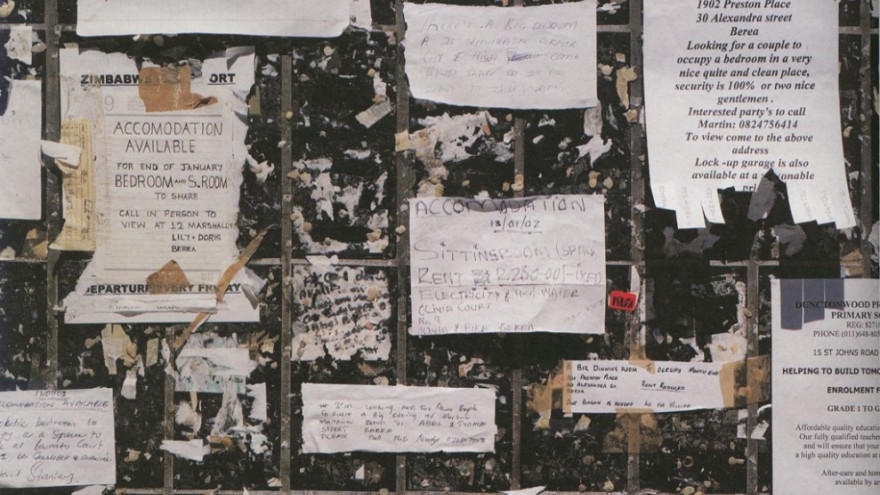

Pause for a moment. Park your car where it is not prudent. Take a stroll through the aftermath of the twentieth century. Wander through the shadows of downtown Johannesburg - tall and mostly 'to let'. ('Toilet,' some joke.) Try gain access to the security cordoned office parks of Midrand, or visit a friend in the nervous suburbia of the North. Dare to negotiate the uncertain bohemia of Hillbrow. And while you are engaged in this reverie, why not visit the unremarkable RDP landscape of Evaton West. It is the same as every other housing scheme for the poor - but also different.

This is Johannesburg. South Africa. Maybe you could even say it is a microcosm of the world.

Cynical? Maybe. But sometimes it is hard not to be. Our romance with the built environment has soured. Today architecture needs to offer us more than just fad, or fake columns. Architecture must embody hope, meaning - not simply brute form.

Sean O'Toole approached two prominent Southern African architects, asking them for their thoughts on architecture and sustainability.

Revel Fox

South Africa's RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme) communities are quickly establishing the domestic landscape of the future. What are your thoughts on the design of these individual dwellings units?

The illusion that South Africans have of unlimited space must be dispelled. Single residential accommodation for urban living, particularly for the indigent, is an enormous extravagance. Because many are first generation migrants from rural settlements, sociologists and urban consultants have encouraged single residential layouts. They accommodate shacks and starter houses and provide opportunities for incremental growth to accommodate extended families. The costs of attenuated infrastructure, roads and services to accommodate poor people who can't afford the commensurate rates is such that, either the services are inadequate, or the local authority bankrupts itself. There must be a major concentration on compact urban housing, properly designed, and providing the higher level of service and amenity that such settlements can better afford. The efficiency of much shorter walking and commuter distances is a major benefit.

BREEAM, a well-known building assessment method, emphasises that wherever feasible architects should use construction techniques indigenous to an area, learning from local traditions in materials and design. How often does this actually happen locally?

The hopeful signs are in the fashionable new generation of game lodges and wilderness hotels where good examples abound of building with local materials using vernacular references. All indigenous rural architecture was and is built that way. Its growth into semi urban situations should be encouraged.

It is also easy to find examples of sustainable architecture if we look back to before the days of cheap energy. Many of us spent childhoods in houses which collected rainwater in storage tanks, discharged grey waste water onto vegetable patches, lived comfortably with pit latrines, cooked on wood or anthracite stoves, generated some electrical power from wind chargers or solar panels, etc. While some of these practices persist in remote and arid locations, the ubiquitous presence of Eskom power and piped water defy most attempts to respond to the growing demand for sustainability in practice.

It is worth mentioning the work of Hassan Fathy. In 1969 he recommended the use of mud brick and mud vaulting, still practised in parts of Nubia, as a solution for mass housing for the poor in a settlement in Egypt called New Gourna. Fathy's book, Architecture for the Poor, describes the use of ancient techniques and planning principles in contemporary urban housing at a high density, and was widely acclaimed.

The intellectual C Thomas Mitchell, in Redefining Design (1993), wrote that contemporary architecture is "bankrupt, the profession itself impotent, and the methods inapplicable to contemporary design tasks." What is your response?

His comments may seem fully justified if one looks at contemporary built environments. Much development, particularly housing, occurs without, or with minimal involvement of the architectural profession. To this extent, the profession is excluded rather than impotent. When it is involved in any commercial enterprise, market forces usually drive the concept rather than considerations of design, conservation or sustainability. There are, however, notable exceptions, with an increasing number of landscape architects, environmental management consultants, architects and planners concerned with an holistic approach to resource management.

REVEL FOX, a partner in the firm of Revel Fox & Partners, is one of Cape Town's leading architects. His architectural work covers a wide range of different building types; from sub-economic housing to luxury apartments; from fine textured, small scale planning to major urban interventions; from comprehensive planning and design for secondary and tertiary educational institutions to very important restoration work. A retrospective exhibition catalogue, entitled Reflections on the Making of Space, provides a comprehensive overview of Revel Fox's contributions to South Africa's built environment over the last four decades.

Michael Pearce

What are your thoughts on the notion of sustainable design?

In some ways it is an oxymoron. Wolfgang Sachs, the author of Planet Dialectics - Explorations in Environment and Development, points out it that development in the Western sense is a real problem. The Western development model is at odds with both the quest for justice among the world's people and the aspiration to reconcile humanity and nature. There are not enough resources for all six billion people. Western development is also premised on a linear consumption model.

How has this thinking filtered into your architectural work though?

My models are all to do with the ecosystem, which is a system in balance. I subscribe to the Gaia Hypothesis, which says that the whole planet is a balanced system. To quote it's chief proponent, Dr James Lovelock: "The entire range of living matter on Earth; from whales to viruses; from oaks to algae; could be regarded as constituting a single living entity capable of maintaining the Earth's atmosphere to suit its overall needs." This hypothesis is fundamental to the way I approach architecture.

Based on this, my architectural idea comprises three components: Nature, Resources and Language. Language is a deep problem because it has to do with culture and communication, all the factors that can potentially be inspirational. The importance here is to reference a people's culture, which is difficult, avoiding kitsch, avoiding falsity.

Your Eastgate project found inspiration in a termite mound. What other local ideas have inspired you?

Shona and Tonga stools. The extraordinary thing about the Shona, for instance, is that they are one of the few African people who built on a large scale in stone. This fascinates me, why they didn't move like the other migratory groups. It might suggest that they found a harmony with nature. The ruins of Great Zimbabwe are an amazing reflection on the culture of the Shona people.

Given what you have just said, do you think it is possible to achieve what Frank Lloyd Wright called, in The Future of Architecture, an "…architecture which grows like nature"?

You have to go back a hundred years to the American construct of nature, Walt Whitman's romantic nature. This idea inspired the garden city, the notion of having your own bit of nature in the back yard. This contrasts greatly with a local understanding of nature. The Western tradition romanticises nature, a place divorced from city. The indigenous Zimbabwean construct of nature is different, and rather harsh. It is a place where the ancestors reside. Wright's idea of nature also differs greatly from my own, which deals with sustainability under crisis. I am searching for a new relationship between man and nature.

Are you a romantic architect?

Oh yes, very much so. I am a Dionysian architect.

MICHAEL PEARCE, of Pearce Partnership, has worked on projects in remote parts of Central Africa, conversions of old buildings in the northeast of England, as well as the design of large-scale city developments in Zimbabwe. Born in Harare in 1938, he is committed to appropriate and responsive architecture, having specialised in the development of buildings which require low maintenance, have low capital and running costs, and utilise renewable energy systems. Eastgate, a shopping mall in Harare, is regarded as a groundbreaking prototype of sustainable design. Using passive control systems, the 55-000m_ complex uses less than 10% the energy used by a conventional building its size. The original design inspiration for the mall is wholly African, and is derived from a termite mound.

Invisible anatomy

Shack. Squatter Camp. Informal Settlement. The domestic landscape of South Africa is described by many names. We asked Karyn Maughan to probe things beyond the veneer of these communities. She returned with two stories communicating one reality

Elda Sityoshwana, 68, moved from Stellenbosch to Khayelitsha in 1985. She has stayed in the same home ever since. Elda stays with her unemployed son Mncedi, 25, in a three-roomed shack in Sikhulule Street, Site C, Khayelitsha. She and Mncedi stay on the same street as her other sons, Alfred Vuyani and Clifton Luvuyo, both of whom live with girlfriends and have children of their own. Elda's old age pension of R620, or the equivalent of US$1.9 per day, supports herself and Mncedi. The family also has a cat, Magiliza, who spends most of his time sunning himself on the carpet.

An estimated half a million people live in Khayelitsha: 80% are unemployed. Approximately 86% of Khayelitsha's residents live in informal houses, also known as 'imikhukhu' or 'tyotyombe'. Built from scraps of sheet iron and timber, these shacks are usually clustered close together, creating a situation in which fires can spread very rapidly. Although some shacks are serviced with electricity, the majority of people still use kerosene stoves for cooking and candles for lighting. Shacks are located in flood plains and transport corridors, on unstable soils and steep slopes, endangering the health and safety of their residents, particularly in the event of natural disasters. The heavy winter flooding of 2001, the worst in 40 years, left several residents dead and thousands homeless.

Elda is proud of Mncedi's welding abilities and points to the shack's burglar bars and security gate as examples of his work. The presence of these carefully welded security structures is not uncommon in Khayelitsha, even the door of a church near Elda's home is protected by a steel gate emblazoned with the Nike tick. According to Elda, they are intended to serve as decorations, rather than a crime deterrents.

In February 2002, a two-year Municipal Services Project study into the privatisation of water, waste management and electricity in Cape Town revealed that historically white suburbs enjoy 100 times the resources available in black townships. In a comparison between Durbanville, an upper-income, predominantly white suburb of about 36 000 people, with Khayelitsha, researchers found that R194 is annually spent on waste services for a Durbanville resident. Only R57 is spent on a Khayelitsha resident.

Mncedi is not the only member of the family with creative abilities. Elda transformed her kitchen cupboard by decorating its shelves with a pink floral plastic tablecloth, which she folded up and then cut into a wavy pattern. She also made the shack's curtains herself.

Mirrors are not a common décor feature in the Site C homes, so the presence of a huge, oddly shaped reflective glass sheet on Elda's lounge wall instantly arouses interest. Elda cannot remember where she got it, but says that she has had it "since 1979". It is slightly cracked, but Elda has no seeming qualms about potential bad luck.

Most Khayelitsha residents still fetch water from taps located throughout the township. While the number of residents with water connections in their homes is growing, there is a non-payment rate of 90% for water services. This results in frequent council cut-offs. According to the Cape Metropolitan Area 1998 State of the Environment Report, uncollected waste in informal settlements like Khayelitsha often acts as a breeding ground for rodents and disease-carrying creatures. Injury, suffocation and death among waste pickers and children have been linked to their exposure to open waste sites, the report said. Red Cross Children's Hospital, a state hospital which predominantly serves children from the Western Cape's less advantaged areas, recently reported that a quarter of its diarrhoea cases are caused by campylobacter, a food poisoning bacteria linked to the poor water hygiene and food sanitation in areas like Khayelitsha.

Most shacks are constructed on ground level, leaving them vulnerable to flooding and making frequent sweeping a necessity. As a result, some homeowners resort to elevating their floors with concrete or raising their doorframes slightly to reduce the amount of dust that blows into their shacks. Linoleum covered floors may make for easier cleaning, but Elda's favourite item in the house is her carpet, which is a faded blue and covered with suns. "It is not sore on my feet and I like the brightness," she says.

Khayelitsha's high incidence of crime is a crisis in the eyes of the Western Cape government, as well as the township's businesses. Provincial community safety minister Leonard Ramatlakane publicly stated in January this year that the distribution of policing resources was skewed in favour of more affluent areas, despite serious crimes being more prevalent in areas where poverty was rampant. Research done at Rape Crisis in Khayelitsha found that all the offenders lived within the same community as the participants in the study, and that, in one third of the cases, the offender was known to the participant. Crime syndicates are alleged to have been involved in the killing of several business owners earlier this year. A perceived powerlessness on the part of the police has resulted in a growing number of "informal justice" killings.

Cape Town's housing crisis reached acute levels in July last year when, in one incident, 200 people briefly occupied vacant land bordering the N2 highway near Khayelitsha. It was the sixth land occupation to occur in the area within a two-week period. The land belongs to the Western Cape provincial administration, which expressed concern that land grabs will damage the process of rapid land release that the city has put in place to address the housing crisis. There are an estimated 22 000 homeless families currently living in Cape Town, and heavy winter rains in July last year only intensified the city's desperate need for adequate housing. According to a unicity spokesman, many of the illegal occupants were new migrants to the city and would not be prioritised over families who had been on waiting lists for years.

ReConstruction

A simple house standing alone against the stark landscape of the RDP. The image lingers, not as an object of shared beauty but yet another horrifying figment of the macabre; the prototypically dull, lifeless, suffocating impulse of grand apartheid. In this case, segregation has unleashed its postpartum on the poor. The house has become a dry social artefact of alienation, and architects and designers the manipulators of renewed torture.

The challenges of reconstruction appear thus, uninspired.

At first glance Reconstruction has failed to provide us with a new vision besides the illusory promise of a house. After the grand stone-and-granite edifices of apartheid's Bantustan town planning, there is a singular distrust of anything monumental or over-arching in design. Perhaps it is because 'visionary' architects like Hendrik Verwoerd haunt us with their absurd theories.

The answer, if one may be so bold to suggest a way out, is not to allow oneself to endlessly repeat a particular mantra which reduces everything all-at-once to an absurd design statement like Mies van der Rohe's dictum 'less is more'.

Take the great 'form versus function' debate. According to Stewart Brand, a proponent of whole systems and a great intellectual influence on the American West Coast, function perpetually reforms form. In other words, one's constructions are reconstructed according to whatever use one may assign them.

We evolve. To start a building, to reconstruct a culture, is to set something in perpetual motion, in an endless process of change. "A building is not something you finish. A building is something you start," adds Brand, whose book How Buildings Learn promotes an evolutionary, pattern element to design that has far-reaching implications for South Africa's current housing crisis.

"Evolutionary design sounds like a contradiction, but it needn't be," explains Brand. "Consider the life history of the porch. From the 1840s onward, porches became a highly popular add-on, eventually adapting into spare rooms ... garages also adapt, eventually into extra storage space."

Adaptivity, Brand suggests, thrives on the edge of chaos and is fundamental to our survival. It coexists alongside the evolutionary appeal to an order that thrives on change. Reconstruction, then, is not merely another buzzword, but rather a clarion call to Re-Construct, to Re-Evolve our ideals over time, at the site of struggle - the common home.

One could implode all this wisdom and rebuild our country from scratch, within yet another grandiose Verwoerdian scheme, but like most failures this means up-rooting settlements, moving squatters into townhouses that are too small or too pressured by design constraints to evolve.

Interpreting the ceaseless pattern of South Africa's development extremes is therefore difficult: our schemes are either writ too haphazard and uncontrolled, or too well-ordered and over-planned. Soweto and Khayelitsha stand out as opposite extremes. Is a middle way possible, a strategy of survival that will preserve our idiosyncratic cultural heritage while liberating the potential of the global village?

What this reappraisal of reconstruction suggests, is that evolution is determined by the language we use to describe progress, and this includes the mass media patterns that generate and resolve contemporary images of public appeal. In other words, the medium is the message - exactly like concrete, wood and steel.

The evolution of the common house, remarks Brand, has for all its simplicity, aspired towards an organic-pattern language. It is this language, borrowed from Christopher Alexander's terminology, which infuses reconstruction with an open-ended agenda, and a new poetics - the language of poetry. "Things that are good have a certain kind of structure," Brand writes. "You can't get that structure except dynamically."

David Robert Lewis has previously written about sustainable development for New Ground, a development journal, and was a design and architecture critic for the Cape Times.

House of good hope

"Green architecture is not a style, trend or a vernacular," says architect Andy Horn, echoing a general understanding that sustainable design is more a philosophy of building than a prescriptive building style. And he adds; "Neither is it new."

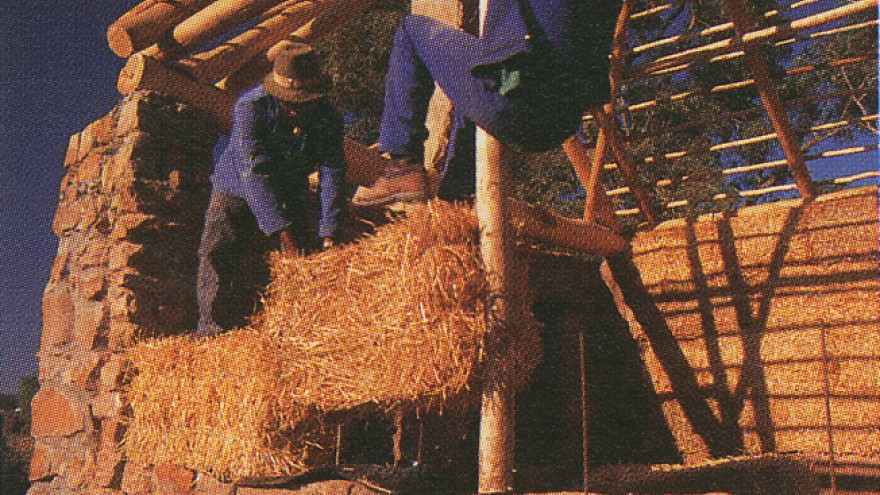

A good example is the straw bale house. Straw, grass and reed throughout the ages served as reliable and easily obtainable construction materials. Quite logical, then, that with the development of the baling machine at the turn of the last century, people saw in the straw bale a useful building material - a natural brick.

The oldest documented bale building was a one-roomed school in Nebraska, built in 1886. The Burke Homestead, built in 1903, still stands defiantly, as does a two-storey mansion in Huntsville Alabama, built in 1938. The most significant benefit of straw bale building lies in the fact that it uses an under-utilised, renewable resource. Furthermore, the embodied energy of a straw bale - being the energy it takes to make and transport a straw bale to site - is considerably less than a brick.

Straw bale walls offer other notable benefits. They are easily and speedily constructed; are structurally sound; are durable and fireproof; and they provide superb insulation. Despite the fact that many South African examples are only evidenced in rural areas, Andy Horn argues that the technique may have some potential for South Africa's low-cost urban housing projects. It is just a case of vision.

Andy Horn, author of A Manifesto for Green Architecture, has built numerous straw bale houses in the Western Cape. A founding partner of Eco Design, he has lectured extensively on sustainable construction and design.