From the Series

First Published in

As an object, food is highly functional. It’s predetermined to solving a problem, the human need for nutrition as a means to live. It is this objective, functional aspect that has Martí Guixé interested in food.

Regarded as one of the pioneers of contemporary food design, Guixé first started looking to food as a design object in 1995. “I was interested in food because I am very interested in mass production as a designer and I realised that food is one of the most mass-produced things around,” he explains.

The Catalonian designer approaches food within the parameters of product design: “I analyse the usability and the ergonomics of it. Next I analyse the social, political and economic context, and collaborate with somebody who solves the technical problems like the taste, texture and manufacturing.”

Likening the process to the making of a plastic chair, Guixé explains that food design needs to understand the context in which it will be experienced: “If you’re sitting in a plastic chair it is because somebody was producing injection-moulded chairs, possibly at a time when it was popular to do so and oil was much cheaper than it is now.”

So, just as it doesn’t make economic sense to be mass-producing plastic chairs anymore, so we need to understand the contemporary context of food, Guixé argues. And that context is one that is continuously changing.

“There’s this ongoing economic crisis, which is also a political issue that really should affect food in a certain way,” he points out. This context is not really in the food we eat or the restaurants that we go to, Guixé continues: “If you want a contemporary take on food you have to reflect the continuous changes in society because only then does it speak about the day that we are living.”

Guixé believes that every object needs to have a level of complexity: “I cannot do an object if I don’t care about all these factors and I need to be able to understand them in a holistic way.” It’s about considering where the object comes from and where it goes after it has been used or consumed.

One of Guixé’s first food design projects demonstrates this belief. “Spamt” takes the Catalan tradition of eating bread with tomato, olive oil and salt, and simplifies the process by turning it into an all-in-one food product.

Understanding the context of food is also important if the combination of food and creativity is going to be applied to improve people’s quality of life. “What we eat is so primitive and so stupid that it must be improved and that is what food design can do, because as a discipline gastronomy goes in the wrong direction. Gastronomy offers a selected experience based only on taste and texture, and doesn’t include the more complex social, political and economic parameters. It just tastes more or less good,” Guixé believes.

“Food Karaoke” was one of Guixé’s projects that urge the user to become part of the political and economic system around the food experience. Users had to follow video instructions, get their hands dirty and get stuck into preparing their own snack, thereby becoming aware of the process of producing food.

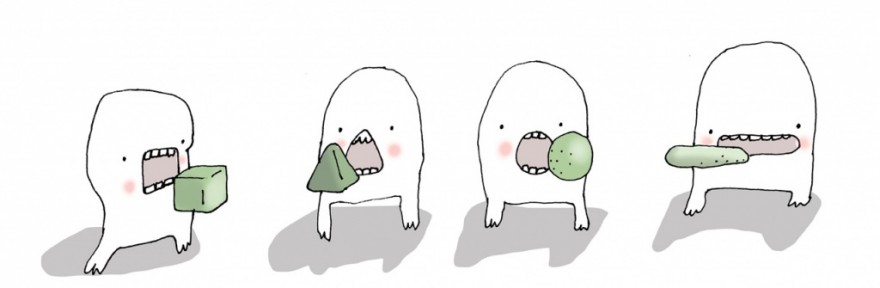

Guixé’s understanding of functionality is extended to the structures that exist around the food industry and our consumption of food. Eliminating any references to cooking, gastronomy and tradition, Guixé is particularly interested in the fact that food, as a product, completely disappears when it is ingested and is then turned into energy.

As such, he has also looked at alternative ways of ingesting food and drink. The “Gat Fog Party” saw an artificial indoor fog made of gin and tonic distributed throughout a room in a misty haze. Thinking beyond taste sensations, the “I-Cakes” saw the ingredients in the cake visually represented on the baked goods in the form of a graph, highlighting the percentage each ingredient contributed to the final product. “It’s decoration becoming information”, reads his website.

Despite these projects seeming to be somewhat theatrical, one of the problems with food design, Guixé reflects, is that it requires a kind of performance. But, he says, “food design shouldn’t be about performance because then it just becomes performing with food and not food design”.

For the moment though, food design is still a very academic thing for Guixé. Making it more accessible to the public is a question of time. “I don’t know how to make it more accessible. It is something that happened slowly. Ten years ago it was completely incredible for a lot of design magazines but now there are schools and organisations teaching food design. But it’s still just the beginning phase, it needs another 10 or 20 years,” he concludes.