First Published in

Kalle Lasn is not your archetypal design personality. Indeed, there is nothing conventional about this award-winning documentary filmmaker's career. As founder of the Vancouver-based Adbusters Media Foundation, and editor of the highly influential magazine Adbusters, Kalle Lasn has emerged as an important critic of contemporary design and media culture. Sean O'Toole spoke to Lasn, asking him about his decision to revive a dusty design manifesto from 1964.

You once said: "Culture Jamming sees itself as one of the most significant social movements of the next twenty years." Can you elaborate?

Yes, to me, culture jamming is much more than a popular buzzword; it is one of the hubs around which global activism has been swirling since the Battle in Seattle. The way I see it, there is a planetary culture gelling for the first time in human history, and the shape of this culture is the number one issue of our time. Right now, it looks as if it will be a dysfunctional, unsustainable, glitzy American culture. But if we can jam it and start generating a different kind of non-commercial meaning from the bottom up, then maybe our future will have a fighting chance of being a decent one.

Why do you speak of a cultural revolution, as opposed to an out-and-out social revolution?

Culture jamming is a battle for the soul of this emergent planetary culture. When you say "social revolution," it feels smaller than "cultural revolution" to me. If anything "social revolution" reminds me of that old Left versus Right political struggle that I am so bloody tired of. As I wrote in my book: "The old political battles that have consumed humankind during most of the twentieth century - black versus white, Left versus Right, male versus female - will fade into the background. The only battle still worth fighting and winning, the only one that can set us free, is The People versus The Corporate Cool Machine."

Don't you find that people are frightened when you use words like revolution?

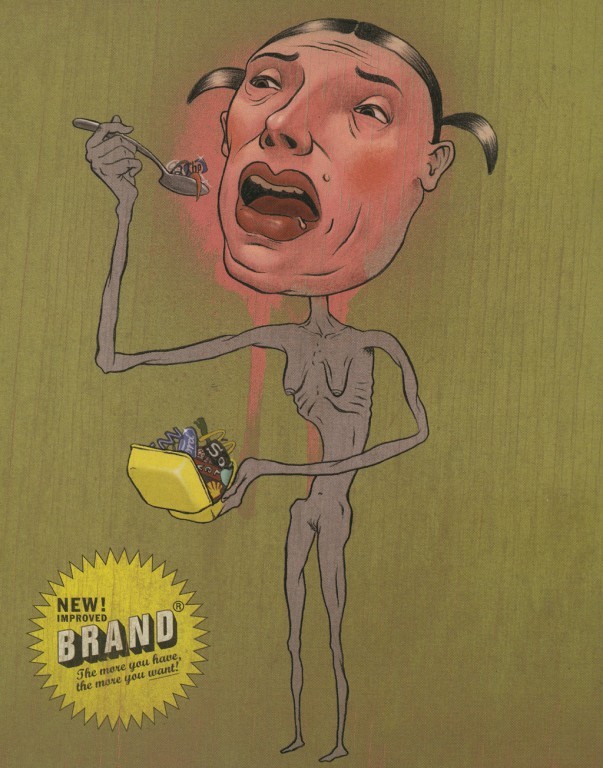

Consumer capitalism is an insidious force that gnaws away at your soul, and if you don't have the boldness of spirit to call a spade a spade, then it is going to suck you up and consume you to the point where there will be nothing left.

How would you sell culture jamming to citizens of a country that has been excluded from the international community for a number of years, to citizens who consciously embrace imported brands as a marker of global belonging?

I don't know if it is possible. I myself was born in Estonia, which was a very dark place for over 50 years, perhaps much like South Africa. Since its liberation from Soviet rule, most Estonians desperately yearn for a piece of the American pie. I don't know if it is possible to talk my fellow Estonians, or South Africans, out of this desire. You will have to discover for yourself the psychological corrosion and alienation that comes with American style consumerism. Until you experience that for yourself, you're a cooked goose.

What prompted you to revive the First Things First manifesto?

For a long time, Adbusters' art director, Chris Dixon, and I were very dissatisfied with the sorry state of visual communications and design. We felt that most designers lived and worked like prostitutes, selling their services to the highest corporate bidders without a second thought. The catalytic moment happened in New York in 1998, when Chris and I dropped in to see Tibor Kalman just before he died. We talked about all kinds of things, and showed him an old issue of Adbusters, the one in which we reprinted the original First Things First manifesto that Ken Garland put out in 1964. After leafing through it, Tibor, in a very casual but telling way, said: "We should do this again." So we did. We decided to stop bullshitting around and debating this thing, and start jamming graphic design.

Was it difficult to get designers like Jonathan Barnbrook or Émigré's Rudy van der Lans to sign up? Or even Rick Poynor.

In a way it was surprisingly easy. The hardest part was coming up with a new version of the manifesto that had a provocative edge and contemporary feel. After going through about 37 drafts, we finally came up with something that felt right. When we sent it out to various designers, with the help of key people like Rick, Rudy and Max Bruinsma, most signed on quite enthusiastically, a few with reservations.

In the May/ June 2001 issue of Print, Rick Poynor commented that "the time for being against things is over … these are propitious times for any kind of criticism, let alone design criticism". He made his comment after mentioning the general apathy among his students. When I however looked at the numerous signatories to the internet version of the FTF manifesto, many of them appear to be students.

Yes, I certainly don't agree with what Rick said there. Looking back to the ruckus the manifesto caused, it was the older designers who nitpicked away at it, questioning phrases like 'new meaning'. It was the young students who continue to email me almost every morning, who visit Adbusters almost like it was a shrine. It was them who found meaning in the design profession. They discovered that design could have an idealistic, even spiritual dimension; that they could use their profession to do some good, change the world for the better; that they didn't have to become servants of corporations. Their passion really surprised me.

Why do you think the manifesto caused such a ruckus when it was published?

The last two or three generations of designers were taught a certain kind of design at school. They were taught that design was a pure, artistic endeavour high above the hubris of life. And they were taught to serve their clients, and suppress their passions and political views. Then we came along and punctured a hole in that view of design. Our manifesto made a lot of designers feel very uneasy, because it called for "the production of a new kind of meaning". It questioned everything they stood for, everything they had lived for.

How do you think designers can help stimulate debate about sustainability issues? How does one communicate long-term outcomes when a lot of contemporary design is aimed at exciting impulse, a very short-term decision process?

Your question feels a little weird.

I think designers and visual communicators are very special, very potent people. They create the look and lure of magazines, the tone and pull of television, the desire and cynicism that drive our economy. Of course there are a lot of other people involved as well, but we designers are the ultimate creators of cool, the ultimate shapers of culture.

You seem to be speaking of the world articulated in Guy Debord's book, Society of the Spectacle.

Yes, yes, yes. That's right. For me it isn't a question of designers being one of many people who come on board and help to win the sustainability fight. These designers and visual communicators and multi-media people, who currently propagate the death culture of consumer capitalism, are the very same people who can show us the way out of this death trap. In this sense, designers have the potential to become the most powerful culture jammers of all. The question is not so much whether they should pitch in and help the sustainability fight, but rather whether they are going to be the tip of the sword, at the cutting edge of the Cultural Revolution.

First things first manifesto (2000)

We, the undersigned, are graphic designers, art directors and visual communicators who have been raised in a world in which the techniques and apparatus of advertising have persistently been presented to us as the most lucrative, effective and desirable use of our talents. Many design teachers and mentors promote this belief; the market rewards it; a tide of books and publications reinforces it.

Encouraged in this direction, designers then apply their skill and imagination to sell dog biscuits, designer coffee, diamonds, detergents, hair gel, cigarettes, credit cards, sneakers, butt toners, light beer and heavy-duty recreational vehicles. Commercial work has always paid the bills, but many graphic designers have now let it become, in large measure, what graphic designers do. This, in turn, is how the world perceives design. The profession's time and energy is used up manufacturing demand for things that are inessential at best.

Many of us have grown increasingly uncomfortable with this view of design. Designers who devote their efforts primarily to advertising, marketing and brand development are supporting, and implicitly endorsing, a mental environment so saturated with commercial messages that it is changing the very way citizen-consumers speak, think, feel, respond and interact. To some extent we are all helping draft a reductive and immeasurably harmful code of public discourse.

There are pursuits more worthy of our problem-solving skills. Unprecedented environmental, social and cultural crises demand our attention. Many cultural interventions, social marketing campaigns, books, magazines, exhibitions, educational tools, television programs, films, charitable causes and other information design projects urgently require our expertise and help.

We propose a reversal of priorities in favour of more useful, lasting and democratic forms of communication - a mindshift away from product marketing and toward the exploration and production of a new kind of meaning. The scope of debate is shrinking; it must expand. Consumerism is running uncontested; it must be challenged by other perspectives expressed, in part, through the visual languages and resources of design.

In 1964, 22 visual communicators signed the original call for our skills to be put to worthwhile use. With the explosive growth of global commercial culture, their message has only grown more urgent. Today, we renew their manifesto in expectation that no more decades will pass before it is taken to heart.*

*2000 Signatories Jonathan Barnbrook. Nick Bell. Andrew Blauvelt. Hans Bockting. Irma Boom. Sheila Levrant de Bretteville. Max Bruinsma. Siân Cook. Linda van Deursen. Chris Dixon. William Drenttel. Gert Dumbar. Simon Esterson. Vince Frost. Ken Garland. Milton Glaser. Jessica Helfand. Steven Heller. Andrew Howard. Tibor Kalman. Jeffery Keedy. Zuzana Licko. Ellen Lupton. Katherine McCoy. Armand Mevis. J Abbott Miller. Rick Poynor. Lucienne Roberts. Erik Spiekermann. Jan van Toorn. Teal Triggs. Rudy VanderLans. Bob Wilkinson.

First things first manifesto (1964)

We, the undersigned, are graphic designers, photographers and students who have been brought up in a world in which the techniques and apparatus of advertising have persistently been presented to us as the most lucrative, effective and desirable means of using our talents.

We have been bombarded with publications devoted to this belief, applauding the work of those who have flogged their skill and imagination to sell such things as: Cat food, stomach powders, detergent, hair restorer, striped toothpaste, aftershave lotion, beforeshave lotion, slimming diets, fattening diets, deodorants, fizzy water, cigarettes, roll-ons, pull-ons, and slip-ons. By far the greatest time and effort of those working in the advertising industry are wasted on these trivial purposes, which contribute little or nothing to our national prosperity.

In common with an increasing number of the general public, we have reached a saturation point at which the high-pitched stream of consumer selling is no more than sheer noise. We think that there are other things more worth using our skill and experience on. There are signs for streets and buildings, books and periodicals, catalogues, instructional manuals, industrial photography, educational aids, films, television features, scientific and industrial publications and all the other media through which we promote our trade, our education, our culture and our greater awareness of the world.

We do not advocate the abolition of high-pressure consumer advertising: this is not feasible. Nor do we want to take any of the fun out of life. But we are proposing a reversal of priorities in favour of the more useful and lasting forms of communication. We hope that our society will tire of gimmick merchants, status salesmen and hidden persuaders, and that the prior call on our skills will be for worthwhile purposes. With this in mind, we propose to share our experience and opinions, and to make them available to colleagues, students and others who may be interested.**

** 1964 signatories Edward Wright. Geoffrey White. William Slack. Caroline Rawlence. Ian McLaren. Sam Lambert. Ivor Kamlish. Gerald Jones. Bernard Higton. Brian Grimbly. John Garner. Ken Garland. Anthony Froshaug. Robin Fior. Germano Facetti. Ivan Dodd. Harriet Crowder. Anthony Clift. Gerry Cinamon. Robert Chapman. Ray Carpenter. Ken Briggs.