Part of the Project

First Published in

“Cultivating consciousness since 1995,” Futurefarmers is not just a legendary pioneer in new media design. Founded by Amy Franceschini, this multidisciplinary studio has worked across print, digital and art on the commercial front but, more significantly, finds its vocation in activating communities for social change.

As principal Futurefarmer, Franceschini herself has become widely regarded in design and art arenas. From the speculative Photosynthesis Robot and the anarchic Reverse Ark, to the whimsical Shoelace Exchange and the scientific Lunchbox Laboratory, her work engages with issues of globalisation, politics, environment, community and the human-nature relationship. However, it is her long-term public engagements such as Victory Gardens and Free Soil that best express her commitment to “actionism”.

Franceschini tells Design Indaba how to go beyond temporal design objects to design social change.

You studied fine art. How have you come to use design for activism and what led to the founding of Futurefarmers in 1995?

I see design as a tool for organising. Historically one might say that art has been a means to formally represent ideas; to create thought-provoking images that challenge an observer’s preconditioned perceptions of reality and become hypersensitive to their surroundings. I go one step further and beg those observers to take action. I did not formally study design, but I have learned a lot about the design process through my involvement in commercial design jobs and relations with the advertising engine. It has been an important guiding force in building critiques of that very industry.

I founded Futurefarmers as a means to house several interests under one umbrella. In 1995 the media was blasted with the possibility of cloning a sheep. In 1996 this actually happened. During this media hype, I felt a profound desire to focus on the future of farming, and the social, political and economic implications connected to this idea.

Apparently the name “Futurefarmers” comes from your childhood. What does the “future farm” inherent in the name look like in your mind’s eye?

The future farm is a contradiction. It is a place caught between a survivalist back-to-the-land ethic and innovative uses of existing technology.

The future farm is a distributed project authored by everyone. We must all have a hand in this harvest through backyards, front yards, rooftops, greenhouses and hydroponic farms. We will need all types of farming to sustain the growing population, but the Futurefarm will be a place to contemplate the sensitive subjects that surround notions of growth, population, economy, etc.

It will be a place where one can hand-harvest just enough food for an evening’s dinner and spin wool from the sheep that we milk for cheese, as well as being a place for understanding the history of science and thinking that has brought us to the time and place where we are now.

The Atlas magazine website was one of the first three websites to be collected by a museum. What was it like working on the internet in the 1990s and how has it changed?

It is interesting to be involved in something before the swell appears. You don’t really know that you are even at the beginning of something. At the time of Atlas, we were making the best of a really crippled medium. It was simultaneously exciting and absurd. Looking back on it, I think the most exciting part was the small number of people involved. We were a very small community.

Now it is very easy to get lost in the vast sea of URLs. I have always tended to shy away from crowds, thus I find my hands in the dirt more often than on the keyboard these days. In the 1990s, I really felt the web was a medium that we were shaping. It was a lot like clay or some mushy material that you could make into what you want. Now I feel it is much more of an established tool.

Your commercial work seems to be primarily digital, while your art and activism seems to be interested in making virtual traits – like community, globalisation, shareware, social interaction, gaming and sustainable environments – tangible. Which came first and what is new media really?

We use whatever media makes most sense to convey an idea. Our commercial work is predominately digital, but that is mostly because that is what clients desire. We enjoy working in the digital domain as a sort of sociological or anthropological research. It is a world we participate in as a means to critique.

There is a very DIY quality to a lot of your work. What is your take on the relationship between aesthetics and communication?

It is a question of over or under design. I am suspect of overly designed objects. It is as if the surface is a lure, but to what? If I am to make a pretty object, I want it to seduce you into something more profound than a hole in your bank account and a boost for the economy. I guess I just want to avoid a false veneer. While I appreciate pretty things and enjoy making them, I want to question the notion of value in material and social terms.

One of your overarching themes is the “perceived conflict between humans and nature”. What is this conflict in works such as in Lunchbox Laboratory, DIY Algae/Hydrogen Bioreactor and Photosynthesis Robot?

What I mean by a “perceived conflict between humans and nature” is something I grapple with myself. In some instances I see the inherent difference between “humans” and “nature”, but I also wonder how our perception of things might shift if we did not try to separate ourselves from “nature” so much.

Beyond all these terribly serious issues there is still a wonderful sense of whimsy in your work – from the Victory Gardens props, the Shoelace Exchange and Bingo Field to your collection of adorable online games. What is the recipe for fun?

It is important to embody “play”. Material humour and play can be an invitation into a more serious conversation. I tend to think of “play” as a very political process. In the midst of play is wonder.

Combining politics and the environment, Free Soil is one of your most recent projects and still in development. What is it and where do you see it heading?

In 2050 (40 years from now and longer than I have been alive) we propose that only the very rich will be able to access food from healthy, fertile soil. All other farms will be hydroponic, supplemented with manmade nutrients and highly energy dependent.

Currently companies can procure and trade carbon credits for minimising their pollutants. Quite possibly in 2050, a similar economy will exist in the Nitrogen Economy. The next frontier of concern will be the production and protection of nitrogen within our soils. At the moment one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gases is the production of chemical fertilisers to feed our depleted soils.

Free Soil proposes to buy a piece of land as a starting point for preserving fertile soil where it currently exists. We have been searching for land with clean soil through eBay and Craigslist. Currently we are developing criteria for where the land is, how clean the soil should be and the history of the surrounding area.

Like fine art, this land will be preserved and held in perpetuity for the purpose of protecting the soil and diversity of the planet. We will need to work with a lawyer to draft this land into a trust. The land will be used to study soil conditions and host research and art projects related to soil science and sustainable agricultural practices.

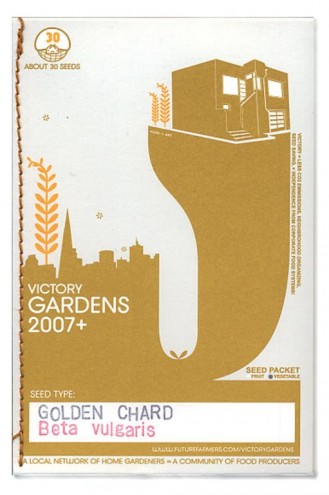

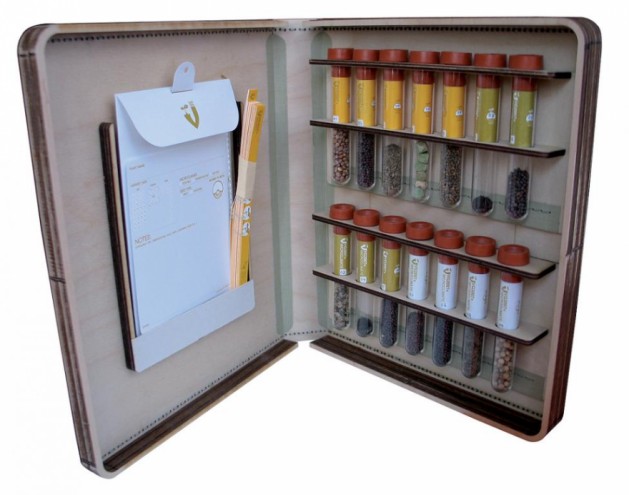

Futurefarmers have also reprised the Victory Gardens from World Wars I and II for the present political and ecological situation. What is the relevance of the Victory Garden to today?

In researching the Victory Garden programmes during the World Wars for the city of San Francisco, the most striking aspect of the historic civic project was the massive participation. Between 1941 and 1943, 20-million gardens were planted and 47% of all the food in the US was being produced in backyards, parks and unused land.

Victory Gardens 2007+ proposes the “victory” as growing food at home for increased local food security and reducing the food miles associated with the average American meal. The project took off as a collaboration with the non-profit organisation Garden for the Environment and the city government, and has triggered a wave of projects including a temporary Victory Garden planted in front of San Francisco’s city hall in the summer of 2008. What started as an artistic proposal has become a policy initiative and a new banner for uniting urban agriculture in the Bay Area.

“Cultivating consciousness since 1995,” Futurefarmers is not just a legendary pioneer in new media design. Founded by Amy Franceschini, this multidisciplinary studio has worked across print, digital and art on the commercial front but, more significantly, finds its vocation in activating communities for social change.

As principal Futurefarmer, Franceschini herself has become widely regarded in design and art arenas. From the speculative Photosynthesis Robot and the anarchic Reverse Ark, to the whimsical Shoelace Exchange and the scientific Lunchbox Laboratory, her work engages with issues of globalisation, politics, environment, community and the human-nature relationship. However, it is her long-term public engagements such as Victory Gardens and Free Soil that best express her commitment to “actionism”.

Franceschini tells Design Indaba how to go beyond temporal design objects to design social change.

You studied fine art. How have you come to use design for activism and what led to the founding of Futurefarmers in 1995?

I see design as a tool for organising. Historically one might say that art has been a means to formally represent ideas; to create thought-provoking images that challenge an observer’s preconditioned perceptions of reality and become hypersensitive to their surroundings. I go one step further and beg those observers to take action. I did not formally study design, but I have learned a lot about the design process through my involvement in commercial design jobs and relations with the advertising engine. It has been an important guiding force in building critiques of that very industry.

I founded Futurefarmers as a means to house several interests under one umbrella. In 1995 the media was blasted with the possibility of cloning a sheep. In 1996 this actually happened. During this media hype, I felt a profound desire to focus on the future of farming, and the social, political and economic implications connected to this idea.

Apparently the name “Futurefarmers” comes from your childhood. What does the “future farm” inherent in the name look like in your mind’s eye?

The future farm is a contradiction. It is a place caught between a survivalist back-to-the-land ethic and innovative uses of existing technology.

The future farm is a distributed project authored by everyone. We must all have a hand in this harvest through backyards, front yards, rooftops, greenhouses and hydroponic farms. We will need all types of farming to sustain the growing population, but the Futurefarm will be a place to contemplate the sensitive subjects that surround notions of growth, population, economy, etc.

It will be a place where one can hand-harvest just enough food for an evening’s dinner and spin wool from the sheep that we milk for cheese, as well as being a place for understanding the history of science and thinking that has brought us to the time and place where we are now.

The Atlas magazine website was one of the first three websites to be collected by a museum. What was it like working on the internet in the 1990s and how has it changed?

It is interesting to be involved in something before the swell appears. You don’t really know that you are even at the beginning of something. At the time of Atlas, we were making the best of a really crippled medium. It was simultaneously exciting and absurd. Looking back on it, I think the most exciting part was the small number of people involved. We were a very small community.

Now it is very easy to get lost in the vast sea of URLs. I have always tended to shy away from crowds, thus I find my hands in the dirt more often than on the keyboard these days. In the 1990s, I really felt the web was a medium that we were shaping. It was a lot like clay or some mushy material that you could make into what you want. Now I feel it is much more of an established tool.

Your commercial work seems to be primarily digital, while your art and activism seems to be interested in making virtual traits – like community, globalisation, shareware, social interaction, gaming and sustainable environments – tangible. Which came first and what is new media really?

We use whatever media makes most sense to convey an idea. Our commercial work is predominately digital, but that is mostly because that is what clients desire. We enjoy working in the digital domain as a sort of sociological or anthropological research. It is a world we participate in as a means to critique.

There is a very DIY quality to a lot of your work. What is your take on the relationship between aesthetics and communication?

It is a question of over or under design. I am suspect of overly designed objects. It is as if the surface is a lure, but to what? If I am to make a pretty object, I want it to seduce you into something more profound than a hole in your bank account and a boost for the economy. I guess I just want to avoid a false veneer. While I appreciate pretty things and enjoy making them, I want to question the notion of value in material and social terms.

One of your overarching themes is the “perceived conflict between humans and nature”. What is this conflict in works such as in Lunchbox Laboratory, DIY Algae/Hydrogen Bioreactor and Photosynthesis Robot?

What I mean by a “perceived conflict between humans and nature” is something I grapple with myself. In some instances I see the inherent difference between “humans” and “nature”, but I also wonder how our perception of things might shift if we did not try to separate ourselves from “nature” so much.

Beyond all these terribly serious issues there is still a wonderful sense of whimsy in your work – from the Victory Gardens props, the Shoelace Exchange and Bingo Field to your collection of adorable online games. What is the recipe for fun?

It is important to embody “play”. Material humour and play can be an invitation into a more serious conversation. I tend to think of “play” as a very political process. In the midst of play is wonder.

Combining politics and the environment, Free Soil is one of your most recent projects and still in development. What is it and where do you see it heading?

In 2050 (40 years from now and longer than I have been alive) we propose that only the very rich will be able to access food from healthy, fertile soil. All other farms will be hydroponic, supplemented with manmade nutrients and highly energy dependent.

Currently companies can procure and trade carbon credits for minimising their pollutants. Quite possibly in 2050, a similar economy will exist in the Nitrogen Economy. The next frontier of concern will be the production and protection of nitrogen within our soils. At the moment one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gases is the production of chemical fertilisers to feed our depleted soils.

Free Soil proposes to buy a piece of land as a starting point for preserving fertile soil where it currently exists. We have been searching for land with clean soil through eBay and Craigslist. Currently we are developing criteria for where the land is, how clean the soil should be and the history of the surrounding area.

Like fine art, this land will be preserved and held in perpetuity for the purpose of protecting the soil and diversity of the planet. We will need to work with a lawyer to draft this land into a trust. The land will be used to study soil conditions and host research and art projects related to soil science and sustainable agricultural practices.

Futurefarmers have also reprised the Victory Gardens from World Wars I and II for the present political and ecological situation. What is the relevance of the Victory Garden to today?

In researching the Victory Garden programmes during the World Wars for the city of San Francisco, the most striking aspect of the historic civic project was the massive participation. Between 1941 and 1943, 20-million gardens were planted and 47% of all the food in the US was being produced in backyards, parks and unused land.

Victory Gardens 2007+ proposes the “victory” as growing food at home for increased local food security and reducing the food miles associated with the average American meal. The project took off as a collaboration with the non-profit organisation Garden for the Environment and the city government, and has triggered a wave of projects including a temporary Victory Garden planted in front of San Francisco’s city hall in the summer of 2008. What started as an artistic proposal has become a policy initiative and a new banner for uniting urban agriculture in the Bay Area.