First Published in

Shanghai is known as “The Pearl of the East” and is a city that was designed from the outset. Before the Western powers won concessions from China in the Opium Wars of the late 19th century, there was only a sleepy fishing village. But with the influx of foreigners, the city was built within a walled circle on a bend of the west bank of the Huangpu River.

The city is built around the river and divided into Puxi (literally “west of the Huangpu”) where all of historic Shanghai exists and Pudong (East side), which was farm fields until the 1990s but is currently home to the city’s modern glass and steel behemoths that comprise the Lujiazui financial district. Ferries filled with numerous scooters, cyclists, pedestrians and motorcycles still cross the river but one can see that the tracks onto the boats were designed for cars – a reminder that just over 20 years ago, before the first of Shanghai’s now impressive network of bridges and tunnels, this was the only method of crossing the wide, yellow silt-laden river.

With a population reaching 20 million, Shanghai is the nation’s most populous, and certainly most prosperous, city in mainland China. And despite city planners’ design schemes, Shanghai is a city with a mind and a rhythm of its own.

“Shanghai is fascinating as it exists on multiple levels no matter what sphere you are moving in,” says former Shanghai resident Richard Simpson, who works as portfolio design manager with New Zealand-based Essenze and is an expert in organisational behaviour. “On street level, rickshaws pulling collected polystyrene are mingling with luxury cars, but there is no friction or visible animosity. It clicks and hums at an extraordinary pace and seemingly reinvents itself on an almost daily basis.”

With overflowing sidewalks where pedestrians bump shoulders, spilling into bike lanes where displaced cyclists jockey for space with the endless stream of motorised traffic, including unlicensed three-wheeled taxis, a never-ending stream of electric scooters and motorcycles stacked with produce from neighbouring provinces, as well as cars and buses, the morning commute is a chaos that somehow works on a grand scale.

The traffic patterns found some recent relief due to massive expansions in the subway system in advance of the 2010 Shanghai Expo. It is a safe, clean, cheap and environmentally friendly way to move over 7 million riders per day from one of the more than 270 stations along the over 420 kilometres of track. A ride on the metro starts at 3 Yuan or approximately US$0.45. The longest ride will only cost about US$1.

All of this traffic reflects a huge amount of commerce and the city is growing, expanding and modernising at a breakneck pace. It is happening so fast that rows of vast skyscrapers, each contributing a unique design to the skyline along the main business arteries, give way directly to 19th century “shikumen”, Shanghai’s distinctive brick residential blocks characterised by winding, narrow streets. Meanwhile across the city, former concession areas offer European-influenced villas and Russian Orthodox churches that have been renovated into upscale nightclubs.

“Local and global influences are brought together and blended to infuse the city with a mystique all its own,” comments Simpson. “Traditional Chinese architecture is encroached by modern high-rises, making its command of positive and negative space even stronger. Standing at the Bund [riverfront] is very much the ying and yang of the city with the Art Deco behind and the flamboyant modern expressionism across the river.”

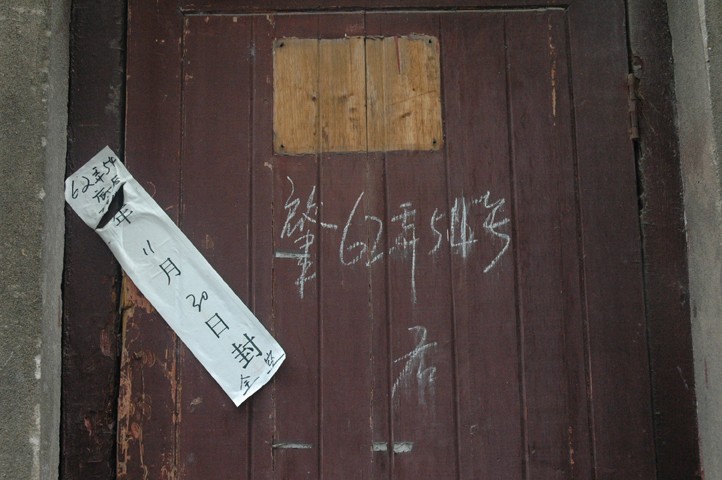

But not everyone is sharing in this prosperity. Gentrification remains rare in this city that strives to be so modern. Instead of repurposing existing buildings, entire blocks are demolished and residents displaced to make way for new buildings. A rundown shikumen block located conveniently along Zhaojiabang Road, a major business street, is a myriad lanes zigzagging among once-stately brick buildings that all bear the white hand-painted Chinese character meaning “condemned”.

Although the demolition has begun, Liu Xiaoling is one of only 10 residents left in her block that used to be teeming with thousands. Here she pays US$62 per month out of her US$200 salary for her 5 square metre single-room apartment. Most apartments exceed her salary. “I look at these beautiful old buildings and it seems like they are weeping and aware of their fate,” says the 34-year-old office maid. “I want to stay in Shanghai, but once this room is gone, I may not find any place I can afford.” Others from her neighbourhood and nearby blocks visit the lottery vendor on her lane in the hope that they will be lucky and avoid their fate.

“Among the chaos there is order of a highly dignified manner,” adds Simpson. “Wet markets on the roadside appear to be a seething mass of people fighting for personal space, yet for the locals they seem to represent a layer of tradition within a whirlwind of change. Designer label stores next to hole-in-the-wall eateries define a city that refuses to lose its roots to rampant building.”

One of the economic realities is that “wet markets” are the local choice for affordable vegetables. At best these are grand open halls filled with local farmers. But there are also lines of farmers that carry their produce to town in two baskets on a bamboo pole and then squat along a roadside, effectively cutting off all traffic and clogging it with pedestrians elbowing their way to a bargain.

Though the Chinese government has strong authority to enact civil control, there is a famous folk saying in China: “The hills are high and the emperor is far away.” This exemplifies the passive resistance that the people present to the government. Wet markets are one example. Shanghai mandated the closing of wet markets while stating supermarkets should start selling vegetables, but supermarket produce costs are considerably higher.

So in this communist nation, the wet markets remain due to market demand. Even though the Shanghai government website still boasts that to improve public health and modernisation, all wet markets would be state-owned by 2006, 80% of the wet markets remain privatised. Shanghai lawmaker Zheng Huiqiang concedes that this goal, with a price tag reaching US$4.5 billion, won’t likely be met soon.

The power of the people can also be seen in a 2003 ordinance to restrict all bicycles from downtown and turn bicycle lanes into additional automobile lanes. The popular resistance from an overwhelming majority of the people led to this policy being abandoned. And even while the government forbids superstition and mysticism, the old traditions find their way to emerge.

On a recent taxi ride, my 47-year old driver, Xu Wei pointed to the Nine Dragon Pillar at the intersection of several streets, and told me the local legend that work was repeatedly halted and the pillar could not be solid until a monk came to exorcise a nest of dragon spirits living there. The monk called on the workers to adorn the pillar with dragons so that the people would know to respect their spirits.

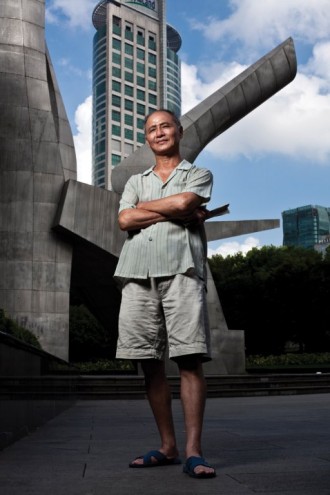

Of course, famed designer Zhao Zhirong tells another story. He was called upon to design the pillar that marks the heart of Shanghai’s sprawling highway network and says he drew on elements from nature like his family’s garden. When he looked at the traffic pattern of Shanghai’s highways, he saw the form of a dragon with wings extended. Nonetheless, locals have propagated the other story and somehow it is fitting of the way the people in this city make their own story.

Richard Trombly is a freelance writer living in China since 2003. He is also an obscure filmmaker with a clear vision at: www.obscure-productions.com

A child of suburban Paris, photographer Patrick Wack has been based in Shanghai since 2006, after spending several years in the US, Sweden and Berlin. Website: www.patrick-wack.fr