From the Series

Judging by the figures, human displacement is a large-scale, global problem. While various bodies and organisations work to ensure that displaced people are supplied with vital resources, there are many other aspects of their wellbeing which is not considered. This made Justin Kim wonder about ways in which aid material that was already there could be repurposed to alleviate some other needs of the millions of homeless, stateless and vulnerable people in the world.

Kim is a recent MA Design graduate in critical practice from Goldsmiths College at the University of London. Intent on “doing something meaningful using design skills” Kim has developed ways of re-inventing the leftovers from refugee aid in eco-friendly ways to benefit these displaced communities.

Kim’s Tipping Point project was a design-led collaboration with UNICEF. The project focussed on reusing and refashioning aid packaging into resources and solutions to improve the plight of refugees. Kim loves the idea that creativity can help solve bigger social and political problems. Inspired by his cardiac surgeon father, Kim set out to make small changes, through various forms of design intervention, to make life more bearable for many people.

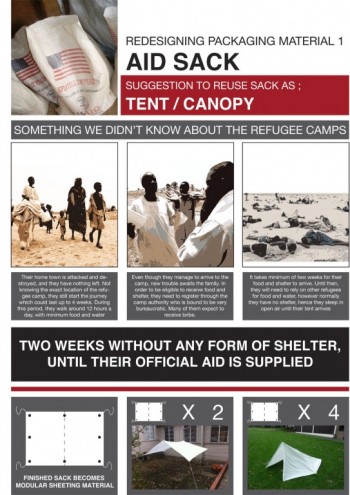

Refugee camps, Kim found, are particularly vulnerable places. Here the people are exposed, both physically and emotionally, but Kim saw this “context as an opportunity for design to be used as a re-directive tool to provide solutions”. The lack of any form of shelter is one of the biggest problems refugees face in the first two weeks in such a camp. Various administrative and bureaucratic hassles often result in no decent protection from the elements, be it extreme heat in the Middle East and parts of Africa, or wind and rain in other parts of the world. Kim investigated solutions for easy and cheap shelter solutions, with a low carbon footprint.

Understanding that a fixed and rigid design solution would not work within the sphere of refugee camps, Kim worked on a more flexible approach that could easily be modified and adapted to the specific needs of various refugee communities. Kim was also adamant that any solution he developed had to work from an open source platform.

The environmental impact and cost of producing a completely new sheltering solution would just be too high to justify socially, so instead Kim worked with what was already available. The aid supplied to refugees by humanitarian groups all come in the same packaging. Whether it’s corn, wheat or rice, the grain sacks are all made with a woven polypropylene material. After cutting, pasting and playing with this material Kim found it be very durable. Further research revealed that the material properties, such as excellent chemical resistance, low density, high heat resistance, low water absorption and permeability to water vapour made these sacks ideal to be repurposed as a canopy to provide shade. With a few simple modifications it could also be used as a tent in cases of emergency.

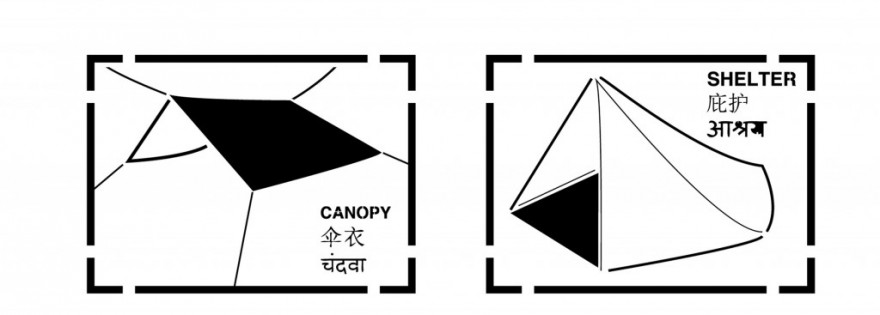

Cutting open one side and the bottom of a grain sack delivers a piece of material roughly 150 cm by 110 cm in size. Kim found that attaching two or more grain sacks together, with the string that comes with the sack, and using a simple wooden stick or pole to support it, the sack material is ideal for shade. While the efficacy of the solution depends, to an extent, on the creativity and resourcefulness of the refugees, Kim also suggests printing basic instructions in the form of pictograms, inside the sack. Pictograms are not only a two-dimensional show-and-tell solution but also a way of overcoming language and literacy barriers.

To be certain of the durability of the polypropylene material, Kim tested his shelters in various weather conditions and found it to be effective, and that it could be extended if camp conditions did not improved after two weeks. Kim also understood the need for a decent waterproof ground covering. This was easily remedied by re-using the large amount of cling film that comes with the aid packaging. Kim suggested gathering enough cling film, rather than dumping it somewhere, to use as the ground covering in the makeshift grain sack tent. The cardboard packaging, in which various other forms of aid are distributed, can then be used as an additional protective layer on top of the cling film ground covering. Cardboard works well as an insulating material, and can withstand a fair amount of wind and rain.

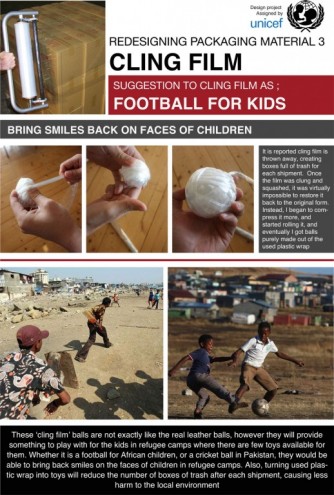

The vast amounts of cling film used to secure aid packaging is non-biodegradable and therefore harmful to the environment. Apart from employing it as a waterproof ground cover material, Kim also played with ways of rolling the cling film into a ball. Refugee children can shape the balls to the size they wish. A material that otherwise would have to be disposed to a landfill site, becomes something that children can use to keep busy and active.

Boredom is said to be one of the biggest social problems in refugee camps. This idleness makes adults and children particularly vulnerable to conflict and other stress-related distractions. Taking his cue from a community of African residents in London that grow potatoes in the sacks they are distributed in, Kim explored the possibility of embedding seeds into the cardboard packaging in which aid is distributed. Nurturing a garden could be a way of keeping some refugees occupied while also growing food and medicine. Kim found that it would be fairly easy to embed seeds into cardboard and that the water-based glue used to secure such boxes would not harm the seeds.

Malaria kits are one of UNICEF’s major aids but Kim found that an effective alternative cure is a plant “Artesmisia Annua” or more casually “Sweet Wormwood”. Kim experimented with embedding the Sweet Wormwood and other plants seeds known to grow well. Knowing that water is often in great scarcity in refugee camps, Kim also tried feeding the seedlings with urine. Unfortunately, the seedlings that were watered regularly grew beautifully but those that received the urine treatment didn’t make it.

Kim’s contract with the UN came to an end in September 2010 but he continues to explore ways of improving the social conditions of people that have been disempowered in various ways.