Filmmaker Ng’endo Mukii made her mark in the world of film and animation with the release of Yellow Fever in 2013. In this talk, Mukii discusses why she chose to use animation and dance to challenge the representation of indigenous people and the consequences of the portrayal of African people as a dead or dying population.

Her exploration of these issues began when she found Gert Chesi’s The Last Africans around 10 years after its release. The book had a profound effect on Mukii because it, like other ethnographic books, portrayed African cultures as either dead or dying. She found that this theme would repeat itself throughout western ethnography because it better suited the need to colonise and “civilise” the indigenous population.

She juxtaposed this form of storytelling with the purpose of a taxidermist. She says that the ethnographer creates the impression of death where life exists while the taxidermist creates the illusion of life where death exists.

Mukii found that this singular narrative had influenced Nairobi’s modern media, which was skewed to western ideals of beauty. One aspect that interested her was the growing trend of skin bleaching. African women would purchase beauty products to make their skin lighter to better emulate the light-skinned women touted as the height of beauty.

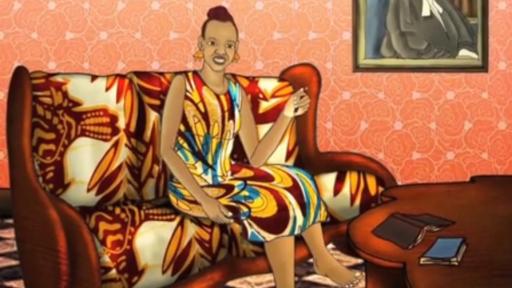

To explore this while steering clear of the stereotypes used to describe African issues, Mukii turned to animation. “I propose the use of animation in relation to indigenous people as a means of telling you that these people are human. The animation is not related to the indexical image and it is able to emulate human emotions and experiences.”

“Animation is not pretending to be alive as is the case with taxidermy, and unlike ethnography it’s not tied to a singular story,” she adds.