From the Series

Quick quick. Tick tock. The time has come. It is 8:25 pm. Wine must be gulped and put aside at the door as we file in to the hall and take our seats in rows of old metal-framed, fold-down chairs with wooden armrests. The dress rehearsal for the South African debut of William Kentridge’s immersive multimedia chamber opera, Refuse the Hour, is about to begin.

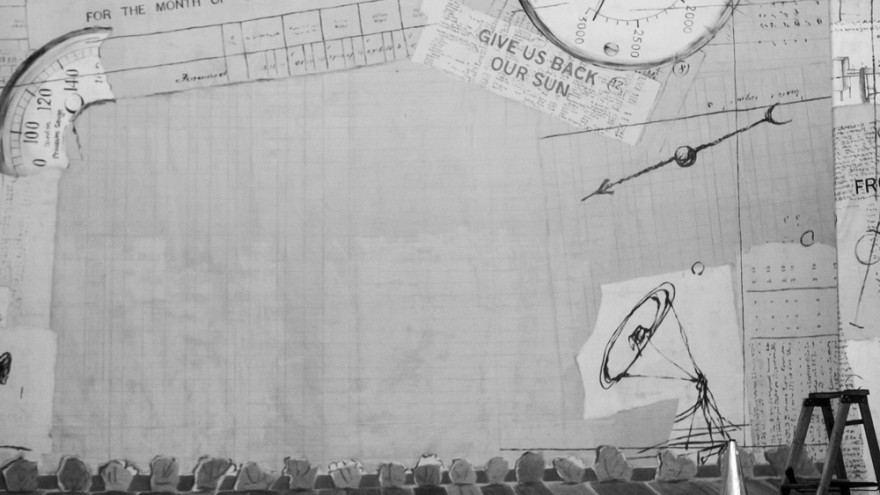

The faded Edwardian grandeur of the City Hall forms an ideal backdrop for the Constructivist stage set with its archival hues and didactic slogans: "argument against authority"; "give us back our sun"; "talking against thinking"... The giant pipes of the old organ rise up over an assembly of musical contraptions, bicycle wheels and megaphones, mechanised drums and other mysterious paraphernalia. We have entered the laboratory of the mad professor in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and we are about to witness an unorthodox experiment.

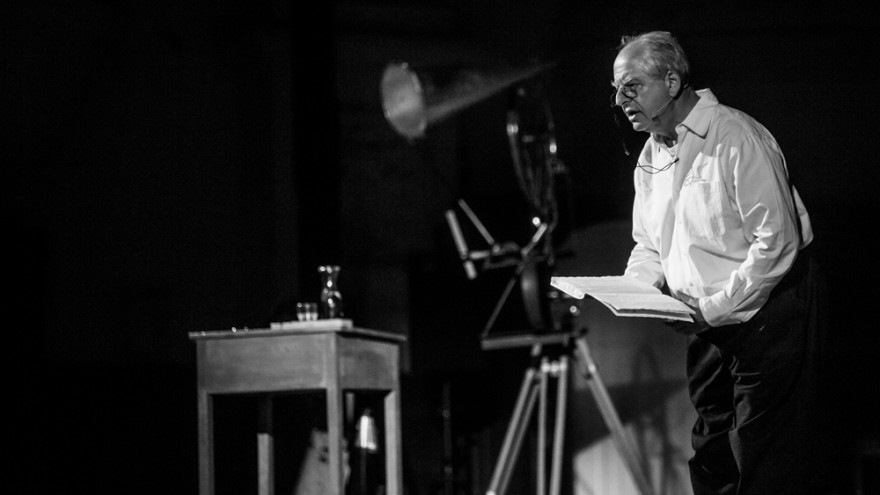

It begins with drumbeats from above – a theatrical flourish, the primal heartbeat, relentless knocking on an unopened door. It begins with a story inside a story; an eight-year-old boy is travelling on a train with his father. His father tells him a tale. It is the myth of Perseus and it has a cruel ending. It is unjust, but inevitable, irreversible. It sets in motion a lifetime of fevered questioning – interrogations concerning the nature of being in time and the inescapable pressure that time exerts on the living. The boy is William – the man we know as Kentridge. And so begins 80 minutes of ecstatic journeying inside the frenetic mind of a creative titan.

The project grew out of a series of ongoing conversations with Peter Galison, a Harvard professor in the history of science and physics, and wrestles with the idea of time moving in a single direction. For physics it can go both ways. The production explores these ideas about the reversal, compression and repetition of time in sonic and visual language.

The auditory aspect is a revelation – transporting the archival bent in Kentridge’s oeuvre into the realm of the futuristic. The ether is abuzz with strange sonic glitches and blips, as echoes are compressed, words reversed, emitted sounds sucked back in on themselves. We are caught somewhere between frequencies on an old transistor radio, picking up the spatial feedback of the universal archive. Of course, the stars and cosmos have always been there in Kentridge’s work, but now an electrifying outward-bound sense of the Russian space station accompanies his backward gaze at the failed utopian thrust of the Constructivists. There is this sense of moving both back and forward – no risk of nostalgia.

Each scene introduces a new thought, a fresh philosophical proposition, and each deserves its own chapter. One such goosebump-inducing moment is the dialectical duet between opera singer and member of the Soweto Gospel choir Ann Masina and sonic glitch artist Joanna Dudley, who is from the Berlin contemporary modernist music scene. There is nothing to prepare one for this strange, alluring dialogue about the birth and death of sound and other things.

Refuse the Hour is a deeply collaborative, multi-vocal production with many layers, many actions and images colliding on the stage at once. It includes dance, performed and choreographed by gifted shapeshifter Dada Masilo, an original score by Philip Miller (who takes to the stage in one hauntingly tender scene, blowing into a plaintive melodica or mouth organ), video by wizard cutter Catherine Meyburgh, mechanical sculptures made in collaboration with Sabine Theunissen, vocal performance and narration.

If you returned to see it several times, each time you’d emerge having resonated with different aspects of the performances, previously unseen shards of the action. Its themes are timeless and also, somehow, pressingly of this moment, triggering a panoply of associations. Some of the connections it called to mind were Achille Mbembe’s meditations on the postcolony as an ‘interlocking of … multiple durées made up of discontinuities, reversals, inertias and swings that overlay one another’; photographer Cedric Nunn’s current exhibition, Unsettled: One Hundred Years War of Resistance by Xhosa Against Boer and British; the time catastrophe, tidal-wave scene in the film, Interstellar (2014); the brilliant androgynous vision of linked lives across time in the filmic adaptation (2012) of David Mitchell’s novel, Cloud Atlas (2004) – but, most presciently, the paradoxically generative idea of the all-consuming force of the black hole which is also at the centre of The Theory of Everything, the Stephen Hawking biopic for which Eddie Redmayne has just taken home an Oscar.

From cropped soviet haircuts to screenprinted aprons, overalls, workerist denim dresses, Cape minstrel fezzes, and the bold black-and-white lines of Xhosa dress design, the costumes by Greta Goris are a swoon-worthy evocation of this mesmerising postcolonial account of time.

Refuse the Hour has aptly been described as "an aesthetic and philosophical stage dream". The word ‘aesthetic’ was appropriated into German in the 18th century and adopted into English in the early 19th, from the Greek aisthētikos, which means ‘perceptive by feeling’. But the term has had a contested history in Western philosophy, coming, ironically, to be applied to the disinterested, distanced, rational act of good judgment about art and the beauties of nature. Phansi to that! Refuse the Hour is a profoundly ‘aesthetic’ production in the original sense of the word in that it gives audiences an immediate, pulsing physical sense of what it feels like to perceive – to know by feeling, to understand through and by the senses. It hijacks the term back from its aloof Kantian deployment and gives it back its social, economic and political potency – its potential for human awakening. Every idea, no matter how complex, is explained, transmitted, made real through the beating, flickering, thumping and soaring effects of sound and light. It is a work made by bodies to be felt and understood in the body – both in the intimacy of our own bodies and in the charged political spaces between them.