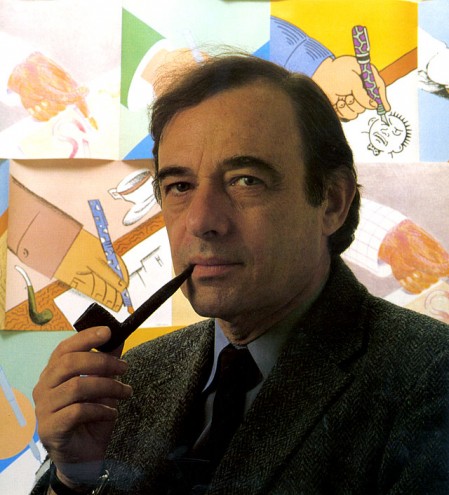

Prolific illustrator and graphic designer Seymour Chwast has been in the business for more than 50 years. In 1954, along with Milton Glaser and Edward Sorel, he co-founded the celebrated Push Pin Studios, which produced some of the most iconic graphic work in the US.

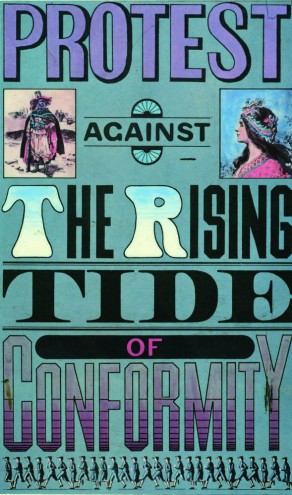

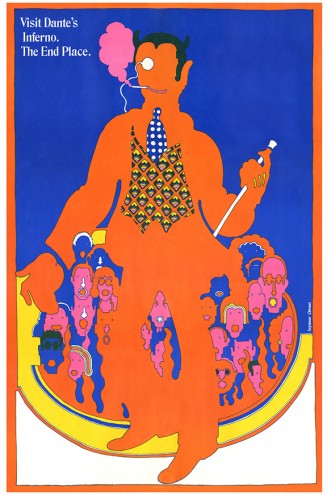

His posters are in the permanent collection of New York's Museum of Modern Art, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, the Library of Congress, the Gutenberg Museum and the Israeli Museum. He was inducted into the Art Directors Club Hall of Fame and is an American Institute of Graphic Arts Gold Medalist.

Fellow graphic designer Steven Heller describes Chwast's work as post-modern before such a term was even coined. “In addition to his unique styles and innovative techniques, Seymour Chwast contributed a delightfully absurdist sense of wit and humour to 20th-century applied art. Although rooted in the decorative traditions of the nascent years of commercial art – notably Victorian, Art Nouveau, and Art Déco – his work is not a synthesis of the past and present, but an invention of the most original kind,” says Heller.

Chwast is a student of graphic design through the ages, many periods of which he lived through himself. His book, Graphic Style: From Victorian to New Century, is a visual survey of its history told only through illlustrations.

Here Chwast reflects on how these traditions and other influences moulded the industry and his work over the years.

Comics and Walt Disney were my earliest influences. In museums I was drawn to German Expressionism, medieval icons in the form of comic strips, the woodcuts of Franz Masereel and the newly emerging flat, but textural, illustration. To me, Saul Steinberg was the god of humorous and conceptual visual expression.

All this found a way into my graphic psyche, which drew the attention of editors and art directors. There was an audience as well for my design during the 1950s and 60s, during which my work adapted to the revival of period styles. After the 1950s, no original movement emerged. Instead, armed with new vigour, Victoriana, Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Surrealism were reprieved. I fell into it with my illustration and design elements with as must honesty as I could, within this new context. Then Swiss Modernism came along, a reaction to all those decorative movements.

After the new versions of the old styles lost their vigour, eclecticism took hold and is still with us today. It has freed the illustrators to follow their instincts and talent while communicating. Design history gained a new importance.

It’s an old story but since the digital revolution, illustration has lost something forever.

It’s sad that work is viewed on a screen rather than on paper. Not to mention what is lost when not viewing originals with their tactile quality.

While illustrators have lost a large market as magazines went under, the undaunted among them turned to animation, comics and their own entrepreneurial spirit to do great work and make a living.

Illustration has had little scholarly criticism, perhaps because it is a poor cousin to “fine art”. On the other hand, design has had no lack of critical study, a relatively new development. For my part I feel that we as designers should hold on to well-worn principles such as scale, proportion and emphasis to make ourselves understood and appreciated in Western culture.

Illustration is not, however, constrained in the same way. Its function is to communicate but with a greater use of metaphor, symbolism and anything else that will make an inspired statement. The range is wide and the results innovative and deep, year after year.