THE LANDLOCKED West African country of Burkina Faso is one of the poorest places on the planet. Whipped by the winds of the Sahara and cursed with poor soil, it has an annual per capita GDP of just $1,200, earned mostly through subsistence farming. It doesn't have diamonds. It doesn't have oil. It doesn't have any of the rare earth minerals that developed countries fight over.

What it has is mud. And rarely, since God fashioned Adam, has that homely element been used to such remarkable effect.

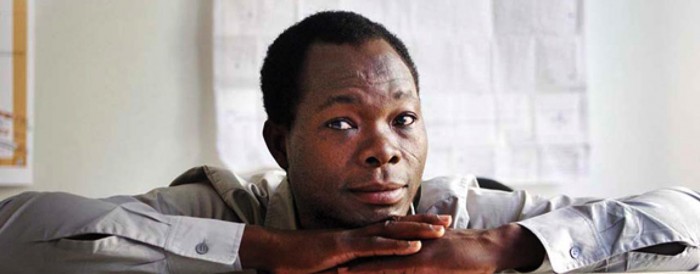

Diébédo Francis Kéré was born in a small village called Gando, about 125 miles southeast of the capital city of Ouagadougou. As the oldest son of the village's chief, at age 5, he underwent a tribal ritual that scarred his face in a pattern of spokes, marking him as both a son and the sun.

Two years later, he was sent off to the city to study -- a rare privilege in his largely illiterate community. When he showed promise at school, he was awarded a scholarship to learn woodworking in Germany, an ironic prize for a student from Burkina Faso. "I was trained in carpentry for a country where there is no wood," Kéré tells me, when I meet him in Cape Town at Design Indaba, Africa's premier design conference. "We're in the Sahara," he says. "We have few trees."

But Kéré recognized opportunity when he saw it and parlayed his scholarship into a high-school degree, followed by acceptance at a German architecture school.

Still, there was a problem. His architecture program was focused on creating structures with sophisticated machinery and techniques in northern climates. Kéré wanted to learn how to build for his own people, in a place where temperatures often top 104 degrees, where there is no electricity for power tools, and where termites quickly make lunch of your two-by-fours.

So he resolved to reverse-engineer everything he was taught, trying to use principles of heat to figure out natural cooling and learning to design windows that would protect from the blazing sun but still offer ventilation.

While in Germany, he learned that the school in his village was near collapse. Determined to help, he launched an organization, Schulbausteine für Gando e.V. (School Building Blocks for Gando) to raise money for a new facility that could give his people a chance at a better life. "Being in the world was a big shock for me," he admits. "How can you explain life in Europe to a community with 99% illiteracy? You cannot tell them about a highway, a plane, about cold water in a glass. But you can give back. And you have to start with the basics, with education."

Kéré was determined not to build the school with traditional construction methods: bunkers of concrete blocks with corrugated roofs that turn into ovens in the summer heat. Instead, he devised a new sort of brick, made of clay, fortified with 10% cement, and compressed by hand tools into sturdy building blocks. These could accommodate a larger structure, survive the annual rains, and support a graceful roof. Now he just needed the labor to raise it.

"The first thing I did was to say to the community, 'I don't swim in money, but I want to do this together, like we used to.' "

The tribal elders were interested but skeptical. "How can we manage?" they asked, when they saw his drawings. "It will be big."

Kéré told them his plan: to work with the climate and with local materials and labor. And he realized he had to get it right. "I knew that if I got it wrong, they would know where I am. They know my family! I can't run away. I had to make it better," he says.

This indigenous approach was important because the area had a long history of Europeans arriving, erecting structures, and leaving. When the buildings fell into disrepair, no one had the materials or expertise to fix them.

But unlike those Europeans, Kéré has a face that radiates optimism, like the sun. He rallied his neighbors, and they set to work. "Everybody was working," he says. "The oldest were encouraging the youngest, the women were carrying water and beating the floors level." On Kéré's index finger, a thick callus developed from drawing plans in the sand.

In six weeks, Gando had a new school for 120 students, made of 30,000 clay bricks. The man who constructed the hand-driven machine that compressed the bricks had estimated that on a good day, villagers could make 700. "At one point, we made 2,000 in a day," Kéré says.

The roof itself was a model of innovation. Corrugated iron, the traditional material, is sturdy and offers great protection from the rain. However, it gets brutally hot. Kéré used what he learned in Germany to create an Eero Saarinen -- like soaring double roof -- one of clay, one of iron -- that was supported by welded rebar and that used natural convection to produce a breeze that simulates air-conditioning.

The structure was so inventive that it won Kéré the 2004 Aga Khan Award for Architecture and the 2010 BSI Swiss Architectural Award. His project was recently featured in MoMA's 2010 show "Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement."

"We were interested in Francis's reimagining of local techniques," says Margot Weller, one of the show's curators. "Because it was built by the community, the community then becomes its steward."

And the project had an unexpected side effect: teaching villagers new skills that they have subsequently used to build schools and housing in other communities.

"What Kéré did is a model for architects working in other parts of the world," says Matilda McQuaid, deputy curatorial director of the Cooper-Hewitt, and part of the curatorial team for the museum's National Design Triennial exhibition,"Why Design Now?" He showed what it means "not to impose, but to make a partnership, to know the culture, and get buy-in. It's a way that Westerners can work hand in hand" with people in developing countries.

Kéré, whose Gando schools now educate 500 children, has also constructed a library and a gymnasium, and is working on a secondary school and a women's center. He's also building an arts village near Ouagadougou. He's not the only Western-trained African returning to his roots. David Adjaye is building a college in his native Ghana, as well as a community center in Johannesburg. And Ghana's Joe Addo is developing low-income housing and designing building products made from local materials such as bamboo and palm kernel shells.

But while Kéré applauds his peers' efforts, his own dream is to promote homegrown talent. Truly scalable architectural sustainability for the region can come only if students can learn Western techniques that are adapted by African schools to indigenous conditions, he says. However, architecture schools are expensive to build, so right now, this is one dream that's beyond the reach of his financing.

"My motto," he says, "is 'help to self-help.' You have to have a dream, start small, and believe."