Text by Michael Godby, University of Cape Town

Produced towards the end of the four-year celebrations of the centenary of the “Great War” of 1914-18, the dramatic art performance of South African-born artist William Kentridge – “The Head & the Load” –explodes the traditional understanding of this conflict as a “World War”.

Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba had famously mocked European pretensions ennobling what he called their tribal conflicts into World War status. Kentridge attacks the idea from a different point of view. His project focuses on the impact this “European War” had on the colonies of the principals. It’s an impact that was ignored at the time and subsequently written out of history.

The British, French and German armies employed hundreds of thousands of African support troops for their war in Africa. The Africans were not allowed to carry arms for fear they might turn against them. Many died from sickness or privation in the course of the war.

As an instance, “The Head & the Load” tells the story of how, when the railway and other forms of regular transport from Cape Town to Lake Tanganika gave out, a ship was dismembered and carried to its destination on the heads of African porters.

The original production of “The Head & the Load” was staged in the massive Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern Museum in London in July this year. It paraded mechanised sculptures and actors. Some bore loads on their head and cast giant shadows before a constantly changing backdrop of animated drawings.

An exhibition of a reduced version is on display at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. “Kaboom!” entails an exhibition of drawings that were used in the original production, with drawings from Kentridge’s staging of both Austrian composer Alban Berg’s opera “Wozzeck” and German artist Kurt Schwitters’ sound poem “Ursonate”.

The collection signals the artist’s deep opposition to the barbarity of war. It also shows his attachment to the language of Dada that evolved at the time to critique it. Walking a ship through Africa is patently absurd.

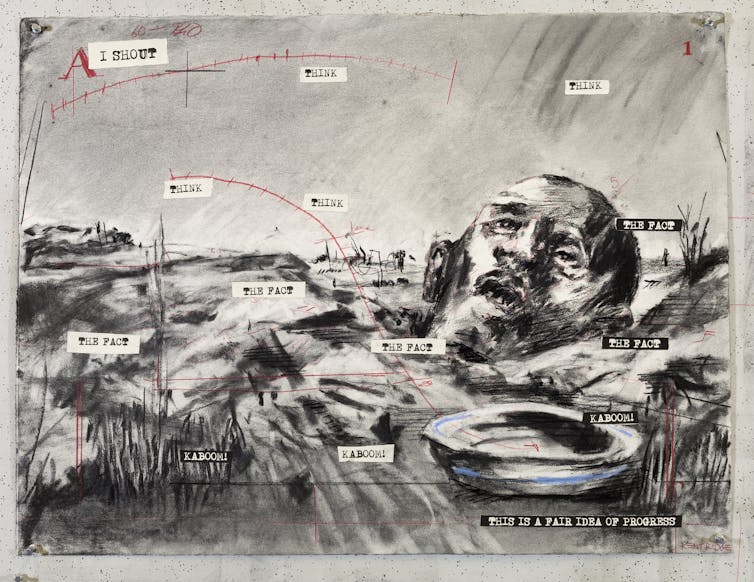

Kentridge underlines the lunacy of the project in every part of the production – from ruined landscapes to caricatural imagery to ironic captions and composer Philip Miller’s fairground-inspired accompaniment. One drawing of a destroyed landscape is dominated by a version of one of the heads in French painter Théodore Géricault’s work “Guillotined heads”. It bears the annotation “This is a Fair Idea of Progress”.

From William Kentridge’s ‘Kaboom!’ Goodman Gallery

Processions

Tellingly, Kentridge interprets the line of porters moving across the landscape as a procession. It’s a motif that he has used often in his work. Processions of the urban poor feature prominently in his early animated “Drawings for Projection” but they take on an absurdist note in works such as the arc drawing “Develop, Catch Up, Even Surpass” (1990, Tate Modern) – as Haile Selassie’s government exhorted the Ethiopian people in 1974 to compete with the industrialised economies of the First World shortly before the Emperor was finally deposed.

The charivari (a noisy mock serenade performed by a group of people to celebrate a marriage or mock an unpopular person), or Danse Macabre element of the procession is developed into dramatic form in “More Sweetly Play the Dance”. It is a 2015 video installation currently showing at Zeitz Mocaa in Cape Town.

It’s also been evolved in monumental scale, in “Triumphs and Laments”, Kentridge’s stencilled dirt drawing on the banks of the Tiber in Rome (2016). In its ephemeral dirt medium, its placement - between the city’s Jewish ghetto and St Peter’s Basilica - and its elaborate iconography, “Triumphs and Laments” seeks to replace a unitary, invariably heroic, account of Roman history by a less glamorous version of the city’s past. In the process, it makes clear that all history is inevitably fragmentary, provisional and partisan.

How history is written

Like the Roman mural, “The Head & the Load” shows that history is written to serve specific interests and that there are always victims of this endeavour.

Correcting the absolutist version of history involves both the deconstruction of the heroic ideal – the demonstration of its fallibility and its dark side – and the bringing to light whole aspects of the past that have been ignored or suppressed.

For Kentridge the Dada procession effects both purposes in appropriately iconoclastic fashion.

The fragmentary and provisional that Kentridge understands as the true nature of history is replicated in his drawing style. It comes to the fore in several parts of the current “Kaboom!” exhibition. In fact, it dates back from the beginning of his career. Kentridge draws quickly in charcoal, refusing the naturalistic tendency of colour and indicating forms and spaces quite summarily.

His “Drawings for Projection” are similarly open and incomplete in terms of both physical definition and narrative sense. Kentridge makes his movies by filming a drawing, altering it slightly, and filming it again to produce the idea of movement until the sequence is finished. He describes this method as “stone-age film-making” whose very “indeterminacy” is a means to refuse definitive reading of any given form, action or narrative.

For Kentridge, this searching and erasure serves a model for understanding our place in the world. It has a profound moral dimension over and above any overt moral in the subject of his drawing or the narrative of his film.

Needless to say, the same indeterminacy that allows the artist to search for the appropriate response to his subject provides an opening, a point of entry for his viewer.

![]()

By Michael Godby, Emeritus Professor, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Watch William Kentridge on the Design Indaba Stage