All of Us Have a Sense of Rhythm presents French/Cameroonian curator Christine Eyene’s original research into rhythmic sources in performative, material and immaterial productions within traditional and contemporary African cultures. The exhibition is the eighth in the Curators Series at the David Roberts Art Foundation (DRAF) in London.

Eyene, who was born in Paris, curated Digital Africa: The Future Is Now for last summer’s Africa Utopia festival at the Southbank Centre and co-curated the Dak’Art biennale of contemporary African art in 2012.

The exhibition encompasses dance, composition, popular music and subcultures and video from the 20th century to the present day.

All Of Us Have A Sense Of Rhythm takes as a starting point the percussive Bikutsi dance music of 1940s Cameroon, and traces the often-overlooked collaborations of modernist composer John Cage with African-American choreographers. From the rise of popular dance subcultures assimilating black music in England (such as 1960s Northern Soul and 1990s drum 'n bass), it points to a contemporary re-appropriation of rhythmic heritage by African diaspora artists in performance and video practices.

William Titley’s “Northern Souls: The Sound of an Underground” (2014) is a recording taken beneath the dance floor of a Northern Soul all-nighter at Victoria Baths, Manchester. The piece captures the unique sounds of the floor creaking under the weight of the dancers rhythmic movements.

Interdisciplinary artist Evan Ifekoya looks at cross-cultural translation in her “Nature/NurtureSketch” (2013), which depicts her in a split-screen video performance of drum ’n bass and African dance moves.

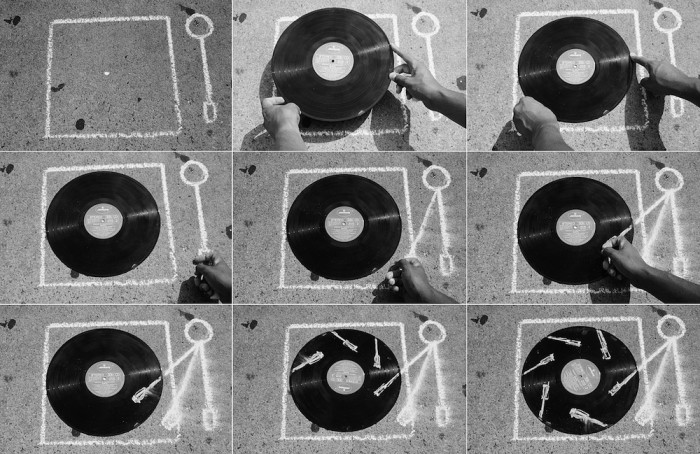

South African Robin Rhode’s photographic series “Wheel of Steel” (2006) shows sequences of a vinyl playing on a chalk-drawn turntable, with the tone arm shifts suggesting the record’s rotation.

Video works by Moroccan visual and sound artist Younès Baba-Ali and Italian sonic artist Anna Raimondo explore non-musical rhythmic patterns using repetitive gesture and voice.

Julien Bayle’s visualisations of rhythmic compositions derive from methods of encoding and algorithm. The music video of “Vessel” by Jon Hopkins remixed by Four Tet, directed by Bison, combines the glitchy syncopated electronic track with a rhythmic editing of fractal anaglyphic images of dancer Claire Meehan’s movements.

“Against this backdrop of cultural assimilation by the Western avant-garde, several recent works in the exhibition see a reclaiming of their African heritage by contemporary diaspora artists,” says Eyene. A selection from British-Ghanaian Larry Achiampong’s collection of Ghanaian Highlife vinyl records, and his sampling and re-presenting of this musical legacy in “Meh Mogya” (2011) and “More Mogya” (2012-13), are included alongside London and Trinidad-based Zak Ové’s hybrid pieces blending hi-fi equipment and African sculpture.

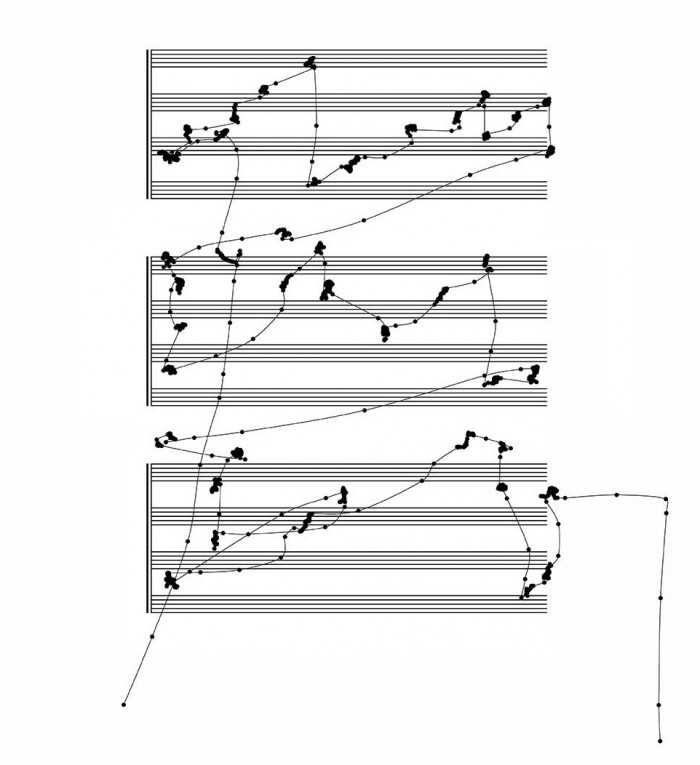

Commissions for this exhibition include Michel Paysant’s “VOX SILENTII (Eye Composing)”, a series of scores created with an eye tracker, a co-production with the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco; and a new piece by Em’Kal Eyongakpa using sound material from recent field recordings in Cameroon.

Live performances of music and dance, film screenings and discussions accompany the exhibition.

Eyene is a guest curator in the DRAF Curators’ Series, which have included exhibitions by curators from Lithuania, Mexico, India and Australia.

All f Us Have a Sense of Rhythm is open until 1 August 2015.