First Published in

The standard incandescent lightbulb has seen little to no innovation in almost a century. While most people will credit Thomas Edison with inventing the lightbulb, it was in fact Sir Thomas Davy who created the first in 1802. Edison was the guy who made the lightbulb practical with the first long-lasting filament in 1880. The last landmark upgrade of the lightbulb was in 1910 with William David Coolidge’s tungsten filament.

Yet, sustainability aside, the design efficiency of a light that emits 95% of its energy as heat, not light – its primary purpose – is low. From a sustainability point of view, this is a waste of energy and wastes even more energy by increasing the need for air-conditioning. Further, the bulbs are not recyclable and last only 750 to 1 000 hours.

The first serious competitor to the standard incandescent lightbulb, from a sustainability point of view, is the compact fluorescent lamp (CFL). We’ve heard all about it: it’s more expensive but uses a third of the energy and lasts up to 10 times longer. Only 30% of energy is emitted in heat. It is claimed that the lifetime of a CFL lightbulb saves half a ton of CO2, compared to an incandescent lightbulb. And, although few people know this, CFLs are recyclable.

It seems like a good option, and certainly the most affordable for now. So good, in fact, that its increasing prevalence has led to a number of countries considering outlawing the incandescent lightbulb. Nonetheless, let’s not get stuck with the CFL for the next 100 years!

Luckily, competitors are already surfacing. Still mainly the reserve for torches and on the obscurer side of the market due to price, LEDs last 10 times longer than even CFLs and 100 times longer than incandescent lightbulbs. Further, they use about a half of the energy of a CFL and produce very little heat.

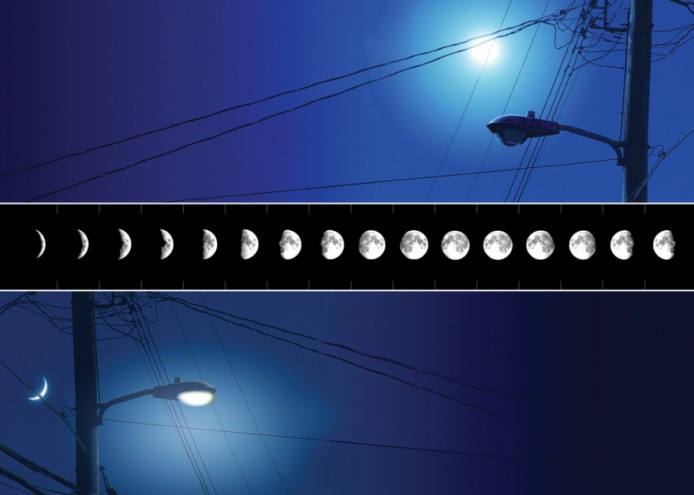

The fact that LEDs provide directional light rather than the dispersed light of CFLs and incandescent lightbulbs has been levelled as a criticism. However, when used in outside lighting, directional lighting reduces light pollution, making the night sky and stars more visible. Further, teaming LEDs with various lenses and clustering formations achieves adequate levels of dispersion.

Still, why use electricity at all? With an input power of 7.5W, using solar-energy-driven power to light your house has become a tangible reality. Several LEDs can operate day and night off energy collected by a small solar panel.

It’s hard to think of someone finding fault with using renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power – especially when teamed with energy efficient LEDs. However, there is an improvement on solar energy, at least during the day. Why use solar energy to produce electricity that then creates light when you can use the sun’s light in the first place?

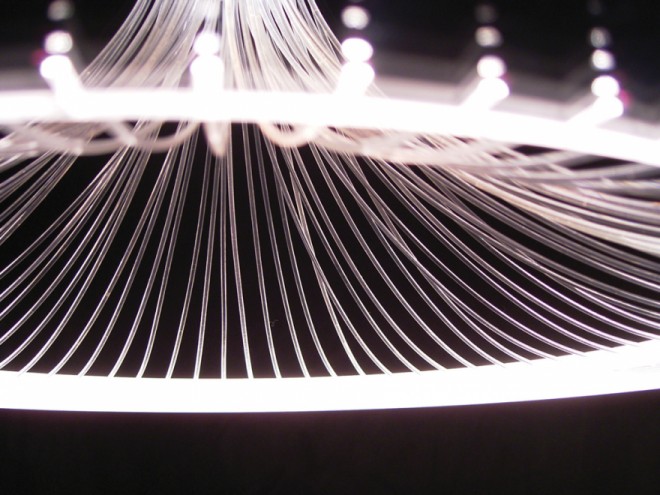

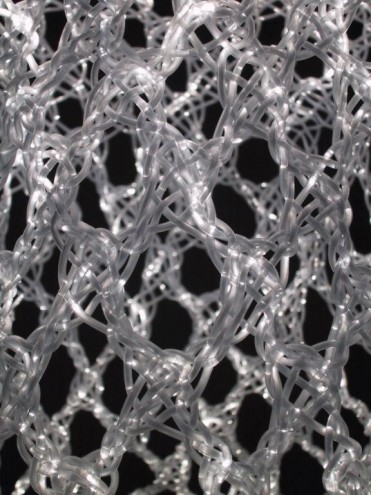

With fibreoptic lighting systems, sunlight can be captured and directed throughout houses and office buildings. Besides the obvious green benefit, the psychological benefits of being in touch with the time of day outside have also been recorded. Further, the uncomfortable infrared and damaging ultraviolet rays are filtered out. On the other hand, there are currently experiments being conducted into filtering everything except the warming infrared light to create fibreoptic cooking and heating utensils.

Overcast days and moonlit nights may leave one in the dark with this system. However, using the same fibreoptic system that captures sunlight, a single-source light can illuminate your entire building. Teamed with a photosensitive reader, the light will automatically brighten or dim to compensate for the amount of natural light available.

Fibreoptic lighting system or not, maximising the usage of natural light is often overlooked and instead flooded out by a ubiquitous artificial glow. The psychological and health drawbacks of this are chronicled widely. By designing the light usage appropriate to the space, not only can you use fewer lightbulbs but improve the general wellbeing.

For instance, lighting ceilings makes rooms look taller and lighting walls makes rooms look bigger. By lighting architectural details and artworks, the visual variety of light can keep eyes (and people) interested and awake, although strong contrasts wear out the eye. Appropriate light shades can disperse or focus the light – consider a lounge as opposed to a study.

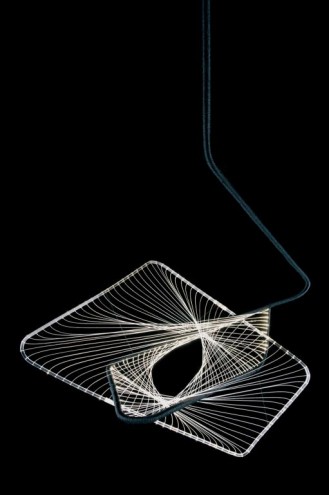

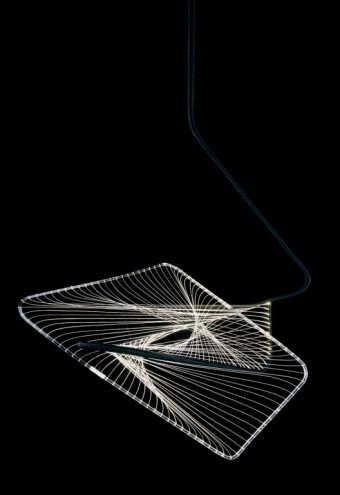

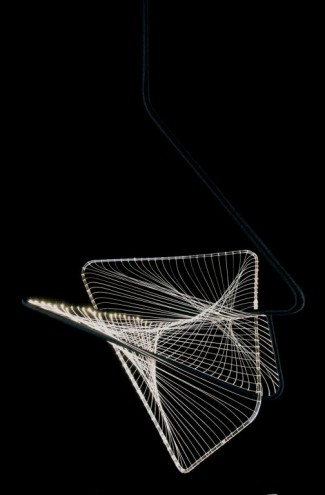

It would be counterproductive to sheath that new energy-efficient lightbulb in a vinyl lamp cover. After designing the space, choose a lamp cover that was produced in an energy efficient manner; made out of appropriate materials – be that re-used, recycled or sustainable; and can be recycled at the end of its lifespan. The light-years matter too – buy local products to reduce the amount of transport involved.