First Published in

"Simple is better than complicated, easy better than difficult, and the obvious better than the construed." That, in a nutshell, is what Dieter Rams expects of good design. It's a formula that this world-famous product designer has always followed in his own work.

Dieter Rams is one of Germany's top industrial designers and a leading proponent of functionalism. Over the years he has amassed an impressive number of awards and accolades. The Royal College of Arts in London appointed him a "Royal Designer for Industry", and awarded him an honorary doctorate; the Industrial Designer Society of America presented him with a "World Design Medal"; and his work has found its way into the permanent collections of design museums like the MoMA in New York, the Victoria & Albert in London and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Born in 1932 in Wiesbaden, Germany, Dieter Rams learned from an early age about the principles of rational design. In his grandfather's carpentry workshop, he saw how great care in workmanship and choice of materials could produce simple but functional design that brought real benefit to the user. These experiences had a formative influence on Rams. They created within him a love of the simple and the unadorned, and led him to take up a career in design. He graduated in interior design at the "Werkkunstschule" in Wiesbaden in 1953, after taking a break of a few years to do an apprenticeship in carpentry. But even during his studies, Dieter Rams started to become more and more enthusiastic about architecture - the path for this was laid by the director of the "Werkkunstschule", Professor Söder, who actively encouraged a link between design and architecture during the degree course.

After college Rams worked first as an architect, and it was in this function that he got a job at Braun's in 1955. The following year, his career in design really began to take off, and over the next four decades at Braun's, his name and success as a product designer became inextricably linked with the fortunes of the company.

Braun's was founded in 1921 by the engineer Max Braun, and made a name for itself as a manufacturer of radios and record players, later also of shavers and kitchen appliances. When sons Arthur and Erwin took over the management they branched out in new directions in communication and product design, and made contact with the University of Design at Ulm. Lecturers Hans Gugelot and Otl Aicher then started to work with Braun's, in cooperation with the university, on developing radio and phonographic equipment, plus exhibition systems and communication tools.

Dieter Rams also benefited from this cooperation and above all, from the very open attitude of the company owners towards design and innovation. Although he was working for Braun's as an architect, he soon became familiar with the design work in the product area. Over the years he gathered a team of people at the company and began to loosen the dependence on the Ulm designers. In 1961 Rams was appointed Director of the Product Design Department, rising seven years later to become Managing Director and a member of the management board. In 1988, finally, he became Executive Director.

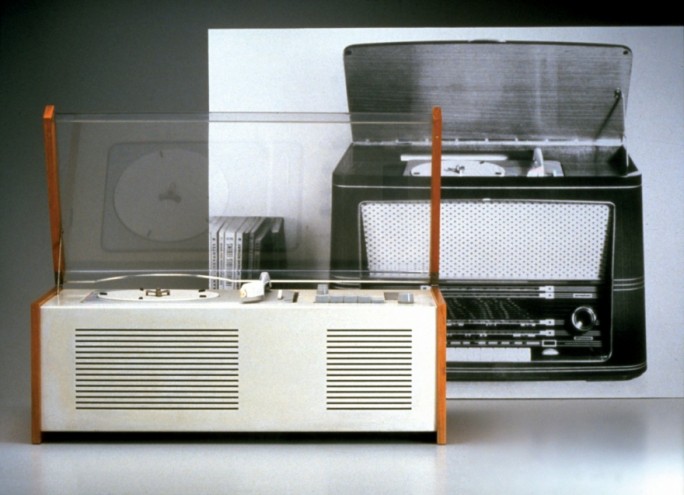

Under Ram's guidance Braun produced an amazing number of products that not only attracted many prizes but also served as models for generations of designers. For example, Braun produced hi-fi systems based on a modular concept, and in 1956 it launched the SK4, a combined radio and record player with a new-style Plexiglas lid (which, incidentally, earned it the nickname 'Snow White's coffin'). Modular systems, the use of metals and plastics, and functional, simple designs - all this set new standards in high-end electronics. In an era, after the Second World War, in which people were having to come to terms with many new things, the entrepreneurs at Braun's had the courage to venture out along new paths, including in product design. In Dieter Rams they found a designer whose striving for the simple and the functional gave their products a distinctive profile and helped make the name Braun synonymous with high quality and sophisticated design.

In an interview for Design Indaba magazine, Dieter Rams talked about his standards for good design, what designers should pay attention to, and how he sees the importance and the future of design.

Do you think the general mood in Germany in the post-war period was also reflected in design?

Yes, this was a time of new beginnings. We were all sick of the hypocrisy of the past and in the post-war climate of change, all things then became possible. One expression of this was the re-founding of the Ulm design school, based on Bauhaus ideas and the new impetus it brought. My intention, as I said, was to break free from past hypocrisy, in architecture, in design and everywhere.

So, in 1955 you started working at Braun's...

Yes, and in the first two or three months I was more involved with architectural tasks. But very quickly I was also given industrial design jobs. The first was for what came to be known as 'Snow White's coffin', which was designed in collaboration with Hans Gugelot and the University of Design in Ulm.

Braun's became world-famous for its radios. What effect did that have on the company?

It meant that the name of Braun was better known. It didn't automatically mean financial success for the company. The radio side had to be supported by other products we were making.

So the company made its money with other products, not radios?

Yes, the cash cows then were flash cameras for amateur photographers, the first affordable ones on the consumer market. Then along came the household appliances, followed only in the early 1960s by electric shavers. But the whole radio business was always in the red. Yet it was the redesign of those radios that made Braun world famous.

Are you saying that although the devices themselves were unusual and attracted a lot of attention, they didn't actually sell well?

There were just too few opinion-leaders around at that time. Most people had to be first brought round to an appreciation of good design. A lot was done, however, to present the products and to make them better known. What did help was the fact that Braun's very quickly received many prizes for its products - at the biennale in Milan, for example, and the Compassadore. These awards helped make Braun a household name around the world.

Would it be true to say that consumers then didn't necessarily appreciate good design?

Not immediately. And I think nowadays it's much the same. Good design always has to be supported by good advertising. However, a great deal of advertising today is either superficial or fairly catastrophic. Design should be communicated through honest information. If design gets more attention these days, it's because of one or two spectacular things, not because of a groundswell of good, informative examples. Basically the whole cultural aspect should be included more. Everyday culture is still very neglected in Germany.

But doesn't good design also depend on the designer finding a company that supports what he or she is trying to do?

Of course. I have always believed that good design is the concern of the whole company and not just the preserve of the individual designer. And over the years my views have only been strengthened. Good, well planned design is becoming more essential than ever before. That has nothing to do with cobbling together some kind of outer casing for the product. Lots of people are involved with each product, and there are lots of different components that go into it. Often these items have to fulfil conflicting functions, yet still form an integrated whole - a whole that is more than its component parts. Achieving this synthesis is today largely the job of the designer and the architect.

Can small companies also achieve this quality of design?

I have a good example of that. It was Erwin Braun that said, let Rams design some furniture as well; it can only help our radios.

Although Braun wasn't even involved in manufacturing furniture at the time?

No, none at all. But the radios were getting more and more technoid and they had to fit into their environment. Erwin Braun's idea was always to create appliances that fitted in with the style of the homes in which they stood, in which they were used.

So you designed a whole furniture concept to suit the radios?

Yes. In 1957 the first furniture designs were done for Vitsoe und Zapf, which was later called just Vitsoe. This expanded as a result of the new designs I did for them, and they are still in existence today. Good design can also help smaller firms to grow. They won't grow into giants, necessarily, but they can expand, and in a way that is healthy.

Would you say that high-quality design is a way for a company to successfully distinguish itself from the competition?

Yes, so long as you are aware that you only reach niche markets. And you need true entrepreneurs, people like Erwin Braun, Wilhelm Knoll and Adriano Olivetti. The ability to think outside the box is thin on the ground nowadays, but if you look hard, you can still find some people who have that skill. Designers must have innovative entrepreneurs at their side, because as designers, we don't work in a vacuum.

Is design an economic factor?

I would say it's not an economic factor, but it's economically significant. Design is coming more and more to the fore. On the technology side, there is in effect little difference between the products, so it's design that becomes the key distinguishing factor. And design has become more popular, although there is still a lot to improve in terms of handling and user-benefit. There's also a lot to do to make things easier to understand and use. One of the main things I try to get across is that good design makes a product easier to understand.

Do your design theories hold true today, and do they also have wider significance?

I believe so. I was amazed a year ago when I presented my ideas to students for discussion, to see just how enthusiastically they were taken up by this young generation of designers.

You yourself are trained as an architect, and became world famous as a product designer. Can the design principles of one field be transferred so easily to another?

For me there is no difference between architecture and other fields of design. Today I would put them together, especially in education and training. And although I have spent most of my professional life in industrial design, I have never regretted having a background in architecture.

But wouldn't you agree that nowadays it's specialisation that is needed?

I really can't recommend this emphasis on specialisation that we see at the moment. The development of new technologies and materials is going to become increasingly important and I believe that the future lies in technology design and in interdisciplinary work. The beauty that is inherent in functional, useful design applies to all aspects of our everyday culture, and it is indeed something that we have to relearn.

For the future I would hope for things that reflect in their overall design the economic and ecological requirements that are becoming ever more important. In short, things that are in harmony with ecology, economics and social responsibility.

Should design always make a contribution to the positive in mankind?

Yes, and this is another of my theories: "Less, but better" means that nowadays we need less and less of the kind of products that are bought simply to satisfy an urge for consumption, only to be thrown away and replaced by others in a short space of time. We need fewer products that malfunction or wear out quickly. Instead we need more of the kind of products that are and do exactly what the users expect of them, i.e. they enhance our daily lives, and make things generally easier.

Where do you take your inspiration from? From nature, or from your everyday life?

It's essential to walk around with your antennas on receive. You have to take it all in - not just the things that nature shows us again and again. And good repetitions are sometimes also a very healing thing. We forget too quickly and are very slow to learn new things.

What would be your advice to young designers?

Designers who can't work with others, whether engineers or other key production people, are lost from the start. Because all those creative ideas will be of no use. Only when I listen to others and take on board their arguments, will they then be willing to accept my arguments. It's that easy sometimes. I think this is one of the key skills a young designer must have. And of course they need a lot of luck and, in the design field, above all staying power, so they are not blown down by the first wind.

What is more important, the content or the tools and way in which it is done?

It's not that black and white. No matter how carefully you do the design, if the technology is unimaginative, the production side inadequate and the advertising poor, the product loses credibility and is ultimately ineffective. There's always this dilemma, and design, too, can often lose itself in superficial things and fashion directions that attract attention for a short period of time, but are at root very transient.

What has to happen before people really grasp this?

I find it amazing that people don't perceive their world more consciously, because we are experiencing increasing visual pollution of the environment. You begin to ask, with just how much chaos can we and do we want to live in future. Appliances, the houses in which we live and the things we need, should all be so discrete and unobtrusive that we hardly perceive them when we are not actually using them. They should blend into any setting in a very neutral, easy way, not causing any visual disturbance and thus enabling us to enjoy using them all the more.

Giving this aesthetic quality to products isn't an easy thing. It never was. This has to be stressed again and again. Unobtrusive, neutral design is not an end in itself, and it doesn't reflect a lack of ideas. It is quite definitely a product benefit. Many users (not consumers), I feel sure, will understand that.

One thing that should not be overlooked is the dimension of time. How much waste can we in fact still allow ourselves? I am, for example, very proud that many of the things for which I was responsible are now collectors items, and that the furniture is still in use. For longevity is something that cannot be achieved through the tools of design alone. A long-lasting product comes from the interaction of intelligent product idea, successful construction, high production quality and well-thought out design. This underlines the fact that design can only be truly successful as part of the overall effort of a company.

If there was one thing that you could remove for good from the world, what would it be?

My answer is quite simple: the spectacular, the hypocritical.